UNHCR Goodwill Ambassador Cate Blanchett has given interviews after returning from her recent trip to Zaatri camp in Jordan to share stories and highlight the importance of continued support of refugees. More images and videos clips has been released.

UNHCR will be sharing stories from her trip across their social media platforms (Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, Tiktok). If you would like to donate, you can follow the link here.

3 questions with Cate Blanchett

What’s an image or conversation that stays with you from your recent trip to Jordan to visit Syrian refugees?

“Last time I was there in Jordan was seven years ago. And when I started to work with UNHCR, the number of people who were internally displaced or externally placed from their homes was around 61 million. And now it’s upwards of 103 million; so 1% of the global population, one in 78 people around the world, are displaced.

“Jordan is a country that has been incredibly welcoming to Syrian refugees in the past 13 years, as has Lebanon. And standing on the high point of the Za’atari camp in Jordan, you see this vast camp which has sort of almost become a city of 80,000 people. You can see the hills of Syria from this camp.”

What does the poem “What They Took With Them” by Jenifer Toksvig capture?

“It captures just how precarious the situation is. And when I was in Jordan — a country that has been incredibly welcoming to refugees — the refugees who are in an urban setting, their situation is incredibly precarious. They’re invisible in a way until you hear them speak. And then Jordanians can hear their accent. And I think with the increasing stigmatization of refugees who are given a label of refugee, it seems to often contain the pejorative sense that they are a burden, that they are a problem, and they are something that needs to be eradicated or sent home or dismissed. I think there’s this terrible pull between needing to be invisible for safety in certain parts of the world, but also wanting to be seen and wanting to be heard.

“They are people who love food, they love football, they love pigeons. They have hobbies. They have an incredible array of skills. The people I’ve met are engineers, they’re doctors, they’re lawyers, they’re people, they’re psychologists, they’re teachers. They’re people who have so much to offer their host community and ultimately communities that either help them return to their homeland when it’s safe to do so, or to be resettled. And I think we forget that. And we forget just how dangerous the day-to-day existence can be for refugees and how important organizations are like UNHCR to provide safety, particularly for women and girls.”

Are there limits to what celebrities can do in these situations?

“I am in no way setting myself up as being an expert in foreign policy, nor on immigration policy. But I do know that since the 1951 human rights convention, everyone has a right to seek asylum. It’s a fundamental human right and it’s a parlous state of affairs that it takes an actor to get a tiny bit of air time to sort of remind ourselves of our own humanity and that our own humanity, those of us who are not refugees, is in peril if we turn a blind eye to inhumane policies being enacted on our watch. It’s a collective international responsibility.

But I think when you hear the numbers, when you know that there’s upwards of 103 million people around the world displaced, it can be overwhelming and you can turn off. My job as a goodwill ambassador for UNHCR is to point to the individual to try and put a human face on the crisis. It would be incredibly important going forward to the Global Refugee Forum that refugees themselves are at the center of the solution, it’s absolutely vital that their voices are heard. Anything that I can do to help provide a platform or to point people to try and listen to that. I think the more one connects, the more one is able to connect.”

In 2015, Cate Blanchett participated in reading the poem “What They Took With Them” by Jenifer Toksvig. You can read the poem here.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that by the end of this year, 117.2 million people in 134 countries around the world will be forcibly evicted from their homes or become stateless. That’s almost 28 million more than two years ago, before Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, before new conflicts like the one in Sudan now.

At the same time, refugee crises like those in the Middle East continue. Combined with climate change, which is also making more and more people homeless, a “toxic mixture” has formed, complains UN High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi. On his behalf, actress Cate Blanchett traveled to Jordan in April as a goodwill ambassador , which alone has rescued more than 743,000 refugees, including 661,800 from neighboring Syria.

S: Ms. Blanchett, you have just returned from Jordan, where you were traveling as a goodwill ambassador for the United Nations refugee agency. What did you experience there?

B: I was there seven years ago. So this time I had the opportunity to reconnect with refugees I had met at the time, but also to meet new refugees, both in the urban environment and in Zaatari camp.

S: Zaatari is the world’s largest camp for Syrian refugees. How is the situation there?

B: On the one hand, it was incredibly inspiring to see how much resilience and optimism there is still, despite the crisis that has been going on for so long. Also, the continued generosity of countries like Jordan and Germany that have taken on such a huge responsibility in hosting refugees continues to be incredible. But I also found it frustrating and disturbing.

S: Why?

B: The refugees who are about to complete what is at best their fragmentary secondary education are full of talent and curiosity. But they will probably not be able to continue their education. I could see with my own eyes that without continued international support, not only will there be an incredible waste of human opportunity, but more problems could arise. After all, it is of course of no use to any country if a whole generation of young people is excluded from education.

S: You speak of international support. Do you feel that Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine has drawn many people’s attention away from the refugee crisis in the Middle East, which continues unabated?

B: The young people I met in Jordan kept telling me: Don’t forget us. They really thought we forgot them. Of course it’s very human. With everything that is happening in Ukraine, what is happening in Yemen, what is happening now in Sudan. UNHCR estimates that if fighting continues in Sudan, 800,000 people could be displaced. And of course they are already internally displaced because they fled South Sudan. Sudan has always been an incredibly receptive country for refugees.

S: Such numbers are hard to grasp.

B: When I started working at UNHCR seven years ago, the number of internally and externally displaced people worldwide was around 61 million. There are now well over a hundred million. This is very difficult for people removed from these crises to grasp. And, as you say, Syria is a protracted crisis. After 13 years you are still unable to master it. It’s too overwhelming. Syria’s neighboring countries bear an enormous burden. There are more than 661,000 refugees from Syria within the borders of Jordan alone.

S: Is Europe doing enough?

B: It certainly has to be commended that countries like Germany, Spain , Jordan and Lebanon – where one in four people is a Syrian refugee – have shouldered a huge responsibility and are setting an example to the rest of the world. A responsibility that is not necessarily taken on by everyone else. No country and no person can solve this crisis alone. But humanitarian aid, a continued humanitarian response, is absolutely necessary.

S: What can you do as an individual – and admittedly privileged – celebrity?

B: My job as UNHCR Goodwill Ambassador is to put a human face to the crisis. For example, when you stand in the Zaatari camp and know that more than half of the 80,000 people there are under the age of 18, you realize: Okay, this really is a crisis. These children are in deep crisis. I respond to that as a mother and on an individual level.

S: How is that expressed? You took your son Iggy with you on your previous trip to Jordan.

B: My son was only eight at the time. We got to know a family in Zaatari, the mother’s sister had been killed, she had taken in her nephew and her niece. They prepared a feast for us the moment they saw us. They didn’t own anything, but brought everything up for us. Iggy used to play soccer with the boys there. But one, his name was Ibrahim, couldn’t play football with them. My son asked me why, and I had to explain to him that Ibrahim’s foot had been destroyed by shrapnel. Ibrahim told us that he still wanted to return home soon. He is the same age as my second oldest son.

S: Do you know whether he managed to return?

B: I met him again at camp this time.

S: He was still there after seven years?

B: He has become the most handsome, engaging, inquisitive, sensitive, generous young man. But he hasn’t gone to school since he was eleven. That’s why he now has the problem that he can’t work, that he can’t study. He tries desperately not to be forgotten and to keep imagining a future for himself. That was a real, tangible, individual reminder for me: how important it is, not just for him, for Ibrahim and his family, but also for the international community, that we don’t allow an entire generation of capable, more enthusiastic people to be left under our watch, hard-working children and young people drop out of the education system and no longer have the opportunity to work.

S: What do these people need most urgently?

B: UNHCR cannot reach all refugees. Its operations are always underfunded, whether in Syria, Sudan, Yemen or parts of Africa. So it is clear that humanitarian aid needs more financial resources. But the most important thing is education. That was my greatest realization on this trip. Education gives hope. Education transforms the energy of young people into something productive. That’s what they need, and they want to know that there are ways to get there. The governments of other countries must help pave the way.

S: How does that work while wars are raging?

B: Of course, the end goal is always peace, isn’t it? One feels like a do-gooder just to mention the word peace these days when so much conflict rages around the world. Nevertheless, there must be safe ways to resettle those affected. They talk about their relatives, their homeland, their desire to return and rebuild this homeland.

S: What needs to be done about this?

B: There can’t be just one or two countries in Europe shouldering most of the burden. It has to be pointed out again and again that unfortunately 74 percent of all refugees are accommodated in poorer countries. There must be no more dangerous ship crossings in the Mediterranean . Those living near the epicenter of the conflict must be supported in housing people close to their homes. Because of course the majority wants to go home.

S: In a country that has been destroyed?

B: That’s all they talk about. They tell about their relatives, about their homeland, about the desire to return and rebuild this homeland. So I think everything the international community can do about it is very important. Despite the xenophobic rhetoric and the notion that refugees are a problem, not part of the solution. But when you meet individual refugees, asylum seekers or even one of the few people who have been resettled, you realize that they are human beings with the same hopes and aspirations as we do.

S: What does this work mean to you personally?

B: It touches us all deeply. I come from Australia, a country that despite its colonial history was built by refugees and asylum seekers. So we have a really interesting cultural melting pot in Australia. But I’ve also witnessed times when that welcoming hug calcified into deep xenophobia. I have seen this turn into an economic and humanitarian catastrophe. With the change of government last year, however, there were positive steps to correct this problem.

S: Xenophobia is spreading everywhere.

B: This rhetoric has also been exported to other countries such as the UK. However, the costs of excluding people are much higher than the costs of integrating people. Cultures grow, people’s horizons expand. The refugees have so much to offer us. When we start changing the xenophobic narrative and starting to see refugees as a positive force in their potential new homeland rather than as a problem, that’s really exciting. It’s very humbling to see how resilient and resourceful refugees are. They see opportunity, while someone like me might only see desperation.

Sources: WBUR/NPR

Welcome to Cate Blanchett Fan, your prime resource for all things Cate Blanchett. Here you'll find all the latest news, pictures and information. You may know the Academy Award Winner from movies such as Elizabeth, Blue Jasmine, Carol, The Aviator, Lord of The Rings, Thor: Ragnarok, among many others. We hope you enjoy your stay and have fun!

Welcome to Cate Blanchett Fan, your prime resource for all things Cate Blanchett. Here you'll find all the latest news, pictures and information. You may know the Academy Award Winner from movies such as Elizabeth, Blue Jasmine, Carol, The Aviator, Lord of The Rings, Thor: Ragnarok, among many others. We hope you enjoy your stay and have fun!

Black Bag (202?)

Black Bag (202?) Father Mother Brother Sister (2024)

Father Mother Brother Sister (2024) Disclaimer (2024)

Disclaimer (2024) Rumours (2024)

Rumours (2024) Borderlands (2024)

Borderlands (2024) The New Boy (2023)

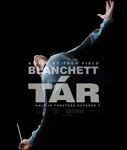

The New Boy (2023) TÁR (2022)

TÁR (2022) Guillermo Del Toro’s Pinocchio (2022)

Guillermo Del Toro’s Pinocchio (2022) Documentary Now!: Two Hairdressers in Bagglyport (2022)

Documentary Now!: Two Hairdressers in Bagglyport (2022)