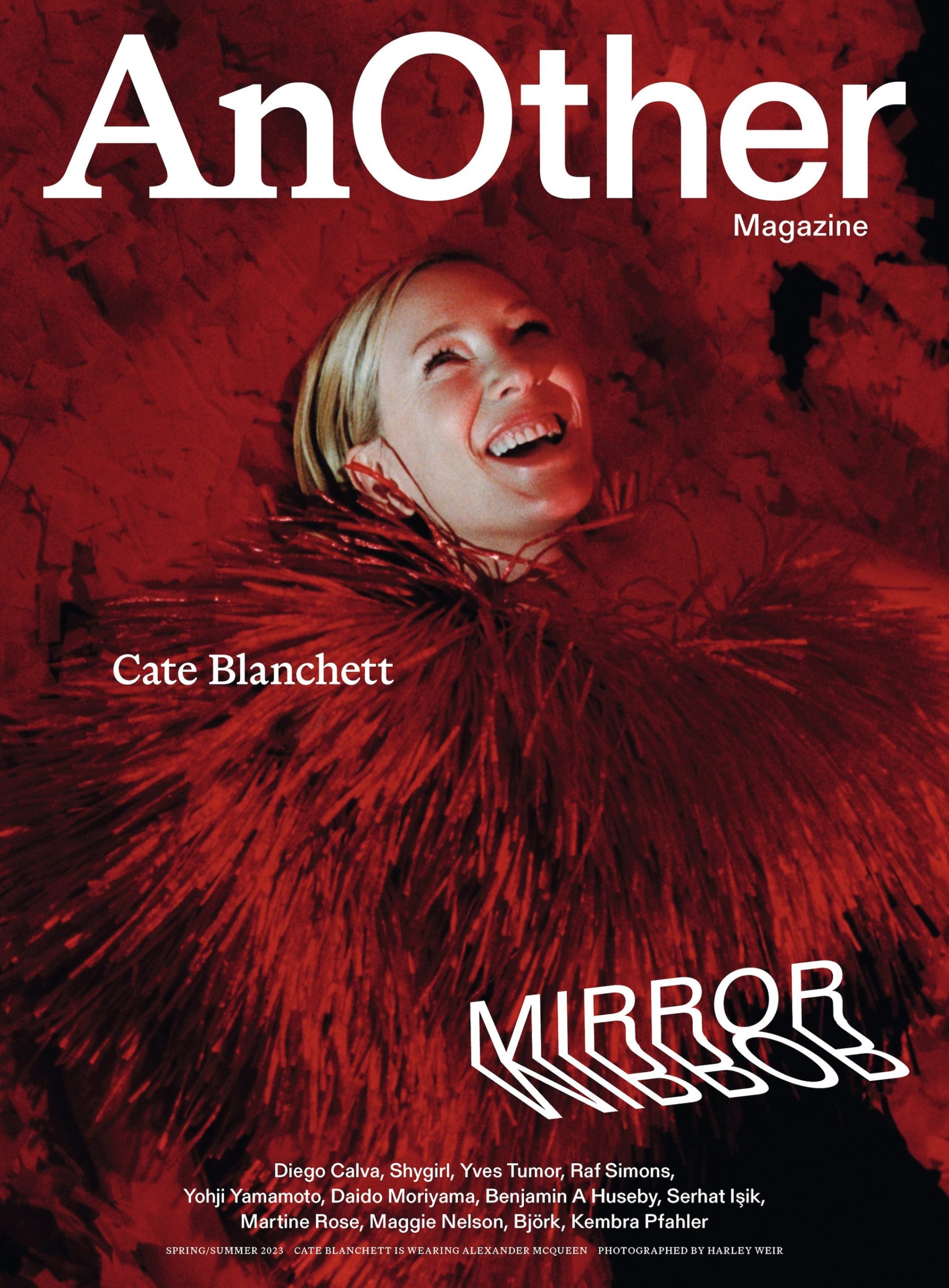

For the second time, Cate Blanchett covers AnOther Magazine, this time the Spring/Summer issue of 2023 and she is in conversation with author, Maggie Nelson. The magazine is on sale worldwide on March 23rd. She is also on the cover the Los Angeles Times’ The Envelope Magazine and spoke about how she is lightly letting go of TÁR and leave it to the audience.

DIVA and MADAME magazines also feature her on their cover plus interviews about TÁR.

You can order AnOther Magazine here, and purchase DIVA Magazine here.

Cate Blanchett: I’m an enormous fan. Let’s just get that out of the way right now.

Maggie Nelson: Stop it. No, I can’t believe you want to even be here on the Zoom with me, but that’s very nice of you.

CB: Well, it’s so interesting to talk to you about this film because you innately understand all the grey areas. I think I struggle with screened narrative sometimes because the idea of narrative often derails the more complicated aspects of the endeavour. It’s as if we go into a maze, or a labyrinth, and we are trained to expect a minotaur in there. I’m not the person to judge what I make – as actors we just do what we do and it’s for other people to interpret. And there’s no right or wrong way to interpret anything, let alone a film. But people have got bound up in the narrative with Tár, which is quite enigmatic and elusive. And Todd [Field, the film’s writer and director] has deliberately not given the audience a definitive answer to anything, but it’s been fascinating to me that certain adjectives have been levelled at the Lydia Tár character and the situation. I’ve thought, “Oh wow, OK, I didn’t think any of that.” But then it’s irrelevant what I think.

MN: What you say about narrative is so interesting – not only with this movie but also more generally – that we’re supposed to be taken through all these nuanced places and then receive a message at the end that makes sense of them. We’re supposed to find, as you say, the minotaur. It reminds me of how, in writing, you can’t really escape narrative – even in experimental, non-narrative writing – but there are a lot of options for delivering the sense of having had a worthwhile aesthetic experience that isn’t necessarily narratively driven.

CB: But even if you are writing in a fragmentary way, is it just that we’re driven as a species to try to order and make sense of it? In a way, narrative exists because people yearn for a path, or we’re taught to make pathways or connections. That’s what I struggle with in the film because it’s very much a process film – that’s the ‘narrative’. It’s a journey, or a musing, or a poking around, rather than an arriving or landing. There are a lot of opposing ideas that are held within the film simultaneously, which is why it is ambiguous.

CB: It is a very confronting thing, admitting where we give our agency away. Sometimes we do that in small, incremental ways and sometimes we do it carelessly. We certainly do it in a compulsive way when you fall in love with an idea or a person. But with Krista I was thinking about Tár as a person who prides themselves on their impeccable judgement. She had made a bad judgement call about someone. She had let her guard down. I never allowed myself to say whether there had been some sexual connection with her because it didn’t feel, in this instance, important to pin down. You can be enmeshed with someone without physical contact – you can be psychologically enmeshed.

So there’s a line when Tár says, “She wasn’t one of us.” And there are a thousand ways in which I suppose you could deliver that line but there was a sense of, “I made a mistake.” I remember someone was talking to me about a young sculptor who was incredibly talented, and his benefactor was saying, “I don’t know that he’s a genuine artist.” And I said, “What do you mean by that?” And he said, “I don’t think he has a sense of longevity. I don’t think he can weather failure.” And I think that, in a way, we’ve all had moments of massive inspiration, but if you live your life as an artist you must be able to be brutal with yourself and weather intense failure. Success in a lot of ways reveals who we are, but you don’t learn much from it. You learn far more from failure. Tár made a misstep with whatever happened with Krista, a misjudgment about her character, and then felt she had to extricate herself from it. And if your identity has been built on having impeccable judgement, or any other quality, and you make a fundamental misstep in that direction, then you start making the decision – from whatever lobe in your brain – to avoid confronting it. You then become increasingly estranged from yourself. In a way, that moment is extrapolated out for the rest of the film – you are dealing with someone who is grappling with failure.

And she’s a perfectionist. And perfectionism is just a stick you can beat yourself with – you can find fault with anything. Tár certainly finds enormous fault with herself.

MN: I like this angle on Tár – that she’s tortured by a misstep in judgement, that the thrill and sometimes horror of being in relation to others is that we can’t know everything there is to know about other people. You can only know as much as you know. The movie definitely brings up the scary fact that no matter how well we think we know other people, or how competent we think we are at judging character, other people are essentially uncontrollable and unknowable. They can always surprise us, and – scarier still – we can surprise ourselves!

I also had a question – it felt important in the film that the Russian cellist to whom Tár gives her attention is an extraordinary player. As opposed to, “Oh, I want to get in this girl’s pants and she sucks but I’ll give her special treatment because she’s attractive to me.” It made me feel like, however flawed Tár’s interpersonal judgement is or isn’t, there is still this question of the natural injustice of merit, of talent, of ability. The injustice that there is somebody that’s better than others at this particular thing and that she is going to get picked out and elevated for it, and that it might seem unfair because Tár seems to have the hots for her, but even in the blind audition, the Russian cellist prevails.

There is a certain weak formulation that leads us to ask questions like, “What’s worth it for great art?” The stronger formulation, it seems to me, starts with admitting to the force that great art sometimes entails – the great concentration or commitment or otherworldliness or sometimes callousness to other demands – and then asking how we are going to negotiate that force in a world in which there are so many other demands on one’s devotion and attention.

Well, especially as women and mothers, we want the fantasy that we can be absolutely everything at all times to everybody and still serve whatever power and talent we feel we have. Sometimes this works out, but sometimes it’s not so clear-cut. In coming to talk to you today, I thought about this question a lot because you, also, are a very talented and very powerful person. You have this force moving through you – this force that is so much bigger than ourselves. We may or may not even know why we have it or what to do with it, but there it is, in a life.

Feminists and women have taken very different tacks to this issue. For example, when I got the MacArthur ‘genius’ grant [in 2016], I noticed in all the interviews that everyone really wanted me to weigh in on the word genius – to say I didn’t believe in it, to disavow it, etc. This has a long and important history, especially in feminism – it’s been important to deconstruct the myth of individual genius, as that myth has been constructed in such a way as to exclude certain bodies and minds from its terms. (See, for example, Linda Nochlin’s famous 1971 essay, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?.) And so, understandably, a lot of people who get that award say, “Oh, I don’t call it that, that’s not the word for me.” But I kept thinking about Gertrude Stein, who loved the word genius and uses it throughout The Autobiography of Alice B Toklas, and I started to wonder what it would be like if I just said, “Oh, I think it’s a great word for me. I totally think I’m a genius.” Not that I feel like that – it was just an experiment, to see what would happen if I didn’t spend time and trouble trying to deflect the word.

CB: But those words have incredible weight. So, because that word is put in your in-tray, you’re forced to deal with it. You’re forced to have an opinion on it. So if it helps me circumnavigate this thing quickly, then I’ll say, “Yeah, sure, that’s fine.” But it’s irrelevant to me.

When you’re in flow, you don’t think about technique, you don’t think about labels, you are just in the middle of the tempest, and you are flying and moving, but then you’ll hit a hump and then you need technique and experience and labels to keep moving. But often we create from a far less literal place. Back to what you were saying about the power of talent – it’s a kind of sorcery. It can, in a way, overtake more susceptible individuals. I think that relates to someone like Krista who gets caught up in the situation and is not able to navigate that – and there’s no judgement in that because I think not everyone can or wants to.

But certain people have an ability and are enlivened and enriched by being in the middle of that tempest, and other people are depleted by it. And in the often-difficult environment of a profession wrought with insecurity and instability and personal confrontation and failure and occasional success, perhaps you need to be able to weather that storm and actually enjoy the instability and be fed by it. I find it hard that people often assume – and I’m sure they do with you, in terms of the extraordinary things you write – that it was ever going to be thus.

MN: Right. And it’s not.

MN: I had the good luck of not having any substantial readership until I was about 42 – I’d written eight books before I wrote a book that a lot of people cared about. And that was lovely because now my other books have been republished, but in my mind they were never any less than the book of mine that got more attention, The Argonauts. I don’t even think that’s my best book. My point is that I’ve seen how books that were, say, rejected by 27 publishers, can be revalued as good and important on the simple caprice of time and market. It reminds me that the moment of acceptance or publication or release is just a moment to get through, it is not necessarily that movie or book’s cultural life.

CB: Well, after we finished, Todd, who has become a dear friend, just put his hand on my shoulder and said, “You shouldn’t work for a while.” Something had happened to both of us through the process of making it. If you’re lucky it happens once, maybe twice in your life – it’s happened to me in theatre and it’s happened to me a couple of times in film – but this was the process of encountering one another and it was all-consuming. And I said, “Oh yeah, you’re right, but I’m just about to work with Alfonso Cuarón … I’m committed to that for six months.”

But there was a real wisdom in that because we’re all part of this constant output, and it’s like, would she please shut the fuck up? Just be quiet for a while. It’s such an important part of the process.

And that’s what I also love about Hildur Guðnadóttir’s score, that in its absence it’s as powerful as its presence. The film has an invisible strength thanks to the parts of the film that Todd has chosen to excise – all those things he decided he didn’t want in the film exist there homoeopathically.

We think about our output and our achievements and the things that people really want to talk about, but in terms of a process and the life of someone who makes things, it’s also about stepping away and percolating. The work continues to happen there. And that’s why when I first read the screenplay I thought the ending was deeply tragic. It’s a real descent. But in the performing of it, it was absolutely exhilarating because I felt it was breaking beyond the canon of, not only the things that a musician should be playing and making and experiencing, but also about her own inner judgement. She had been released from all of that to find out what would happen next.

MN: She really loves conducting and at the end she is still conducting, and having an emotional experience with that. And it seems to me that a group of dedicated cosplaying fans are ready to have a grand experience with the music as much, or more, than anybody in a stodgy Upper East Side concert hall.

CB: You will never see anyone asleep at a cosplay convention. But it reveals the lenses we choose because the circumstances we know about, not only the character I play but all the characters, aren’t finite. Todd and I were hoping that we could somehow just drop this little gem and generate some interesting conversation. Conversation that would probably be fierce and passionate, that people would come at from all different perspectives. We hoped people would see it in the cinema where the ideas could stay big and a little bit elusive.

~ Parts of the conversation; the entire conversation is here.

Cate Blanchett hasn’t watched “Tár” since its premiere at the Venice Film Festival in September. She saw it only one time before, when writer-director Todd Field was ready to show it to her. But it was in Venice, where “Tár”received a thunderous ovation, that she felt something stir inside her. “It started to be painful — I was like, ‘I don’t need to see this anymore,’” she says. “What I’ve learned from it and the takeaway from it, I can’t watch it anymore.”

“It’s almost like we made the film in an unconscious state,” she offers, fighting off the chill of an overcast February afternoon while seated on the rooftop of the Maybourne hotel in Beverly Hills. “We were waking up and saying [to the audience], ‘You know this fever dream we’ve had? That thing that we thought we did, is that how you responded to it?’”

Her memories of “Tár” remain potent: how Field sent her the script, saying that he wouldn’t make it with anyone else; how during her research she’d awake in the middle of the night, only to discover that she had been conducting in her sleep. Now, though, her experience must give way to the audience’s as it takes possession of “Tár,” which she’s thought about a lot.

“[Theater director] Peter Brook says this wonderful thing: You hang on tightly and you let go lightly,” Blanchett observes. “I’ve become better at letting go lightly. But I do look back on the thing, the object, with a touch of melancholy.”

Often during our hourlong conversation, Blanchett will apologize — for being tired, for getting weepy while discussing the film version of “Death in Venice,” for what she perceives as her talking too much. (At one point, she laments, “I will walk away from here yet again saying to myself, ‘Just answer the question. This is not a conversation.’”) As imposing as her performances can be, there’s a touching self-consciousness to her in person — a fragility, a vulnerability — that’s quite disarming. And despite her protestations that she rambles, when Blanchett lets her mind roam free, that’s when the really beautiful insights emerge.

Take, for instance, in the midst of describing Lydia’s complicated relationships, Blanchett eventually arrives at: “Have you ever had this experience — maybe it’s a moment of shame [from] something that you regret doing — but [the memory of it] will often come back to me when I’m driving. It’s like, ‘Why did I say that? What an idiot.’ The thought will come into your head, and all of a sudden you’ll start singing a song to push the remembrance of that event from you? I started to think of music as a way of Lydia pushing her past — or things that she just couldn’t face — out of her mind. The very thing that had been a liberating force in her life was becoming a force that was allowing her not to look at herself, her past and her present circumstances.”

Because “Tár” is a film filled with ambiguities, it’s understandable that audiences and journalists would look to her to explain what they’ve just seen. But Blanchett says that hasn’t really happened — much to her relief. “Mostly, I’ve listened to people who’ve wanted to talk about it, with very little to say myself,” she notes. “I don’t want to get in the way of whatever they brought to the cinema that day. I mean, you look at a Rothko and you go, ‘Rothko doesn’t want to get in the way.’ [Film] is very different, but these works, they vibrate — they’re very resonant. There’s no ‘right’ reading of these works.”

The amount of prep that went into her performance has been well documented. Learning German. Becoming more confident on the piano after having abandoned it as a child. Immersing herself in classical music. But such dutiful recitations can overshadow the impromptu adventures that happened on set. Like when she was told one day that the accordion teacher was waiting for her.

“Todd asked me in preproduction: Did I play the accordion? And I said, ‘What do you think? No,’” she recalls with a laugh. “I said, ‘Do you want me to play?’ And he said, ‘No, no, no.’ And then [during the shoot] Sebastian [Fahr-Brix], the first AD, said, ‘The accordion teacher’s here. Todd wants you to go and sit with the accordion teacher.’”

Confused, she met with Field. “He said, ‘Yeah, you picked up the accordion, right?’ And I went, ‘You said no! I was conducting and learning piano and working with [composer and cellist] Hildur [Guðnadóttir]. No, I haven’t picked up the accordion!’ And he said, ‘Just go and work with it for half an hour.’”

Which is how we got the supremely meme-able moment in which the usually ultra-serious Lydia walks into frame, accordion strapped to her chest, improvising a goofy ditty called “Apartment for Sale.” Blanchett remains deeply amused by the scene. “We did about four takes of it,” she beams. “The rest of the crew, they were looking at each other like, ‘I think Cate and Todd have finally lost their s—.’ He and I were in tears laughing. But that epitomized the collaboration: We would talk and talk and talk, and then suddenly we’d make these really quick decisions.”

In interviews, she sometimes ponders stepping away from acting. It’s hard to know how serious she is — after all, who among us doesn’t need to occasionally give voice to the idea of hanging it up, if only to periodically check in with ourselves? Still, she says of her vocation, “It’s not always a comfortable place to be. It’s very hard sometimes to say no. And sometimes it’s equally as hard to say yes because I have four kids who I am passionate about. I’ve been married for 26 years, and it’s the most important relationship in my life. I have a parallel existence that I don’t want to cannibalize in my work, and I don’t want my work to cannibalize it. I feel incredibly blessed in that way.”

But then the self-critical part of herself pops up again. “You constantly feel like you’re failing both of those relationships, don’t you?” she asks, almost conspiratorially. “The creative relationship and your [personal] relationship. It’s not that I don’t love [acting] — it’s just that it’s …” Another pause. “It’s a very noisy world.” She thinks about all the interviews she gives, how she sometimes will say something to see how it feels to put it out in the air, only to see it later in print, presented forever as some sort of truth. “It feels very disingenuous in this exchange but, yes, I’m constantly wanting to be quiet.”

It’s been nearly six months since Blanchett sat down and watched “Tár,” but that hasn’t stopped fans from repeatedly revisiting the film, hoping to eventually unravel its riddles. She is learning how to let the movie go lightly, which leaves room for others to discover things inside it.

“I was speaking to someone this morning — we were talking about something else entirely, this project we’re doing together — and then he said, ‘OK, just want to ask you a question [about] “Tár.” So the thing where she goes back to her house and she gets the [Leonard] Bernstein tapes out …’”

We’ll omit the rest of what this person said to Blanchett to avoid spoilers — but, suffice it to say, there’s a clue within that scene about Lydia’s nature that many viewers missed. Blanchett’s colleague noticed it, though, and was very excited. So was Blanchett. Recounting this anecdote now, she’s positively glowing, happy to let “Tár” at last speak for itself.

“I went, ‘You got that?!’ I haven’t seen Todd since I’ve had that meeting this morning, but he’ll be so thrilled. It’s those little details that you don’t need to overplay. An audience will pick them up.”

~ Full interview here.

Welcome to Cate Blanchett Fan, your prime resource for all things Cate Blanchett. Here you'll find all the latest news, pictures and information. You may know the Academy Award Winner from movies such as Elizabeth, Blue Jasmine, Carol, The Aviator, Lord of The Rings, Thor: Ragnarok, among many others. We hope you enjoy your stay and have fun!

Welcome to Cate Blanchett Fan, your prime resource for all things Cate Blanchett. Here you'll find all the latest news, pictures and information. You may know the Academy Award Winner from movies such as Elizabeth, Blue Jasmine, Carol, The Aviator, Lord of The Rings, Thor: Ragnarok, among many others. We hope you enjoy your stay and have fun!

Black Bag (202?)

Black Bag (202?) Father Mother Brother Sister (2024)

Father Mother Brother Sister (2024) Disclaimer (2024)

Disclaimer (2024) Rumours (2024)

Rumours (2024) Borderlands (2024)

Borderlands (2024) The New Boy (2023)

The New Boy (2023) TÁR (2022)

TÁR (2022) Guillermo Del Toro’s Pinocchio (2022)

Guillermo Del Toro’s Pinocchio (2022) Documentary Now!: Two Hairdressers in Bagglyport (2022)

Documentary Now!: Two Hairdressers in Bagglyport (2022)