Cate Blanchett is on the cover of TIME magazine’s Women of the Year issue. A gala will be held on March 8th in Los Angeles. She is also starring in the music video of Sparks’ new single, The Girl is Crying in Her Latte, which will debut tomorrow, Friday.

"I thought my use by date when I stepped in front of the screen as a 25-year-old was five years," says Cate Blanchett.

"Of course, there have been trailblazing women behind and in front of the camera who have kept pushing that use by date beyond that" https://t.co/5sSEtwS3dE pic.twitter.com/mdZ0GMHS6h

— TIME (@TIME) March 2, 2023

The video for 'The Girl Is Crying In Her Latte' premieres this Friday and will feature a very special guest alongside Ron and Russell. Who do you think it is? ?#TheGirlIsCryingInHerLatte ? pic.twitter.com/zWc7mWZIDz

— S P A R K S (@sparksofficial) February 28, 2023

“We met Cate Blanchett in Paris at the Cesar Awards last year, little knowing that a year later one of the great actors of our time – and a splendid person – would graciously consent to lending her booty-shaking skills to the first video from our new album,” the Mael brothers said.

“Dreams really do come true. We will sleep well tonight knowing that forever we can say we co-starred in a film with Cate Blanchett.”

Here is a new set of interviews with Cate Blanchett. Some are from German press so they are Google translated to English.

Cate is set to co-chair the Motion Picture & Television Fund annual “Night Before” fundraiser.

That means the Motion Picture & Television Fund is finalizing details for the 21st annual “Night Before” [the Academy Awards] fundraiser that will be held on the Fox lot on March 11, the evening before the Oscars. Angela Bassett, Cate Blanchett, George Clooney, Christopher Nolan and wife Emma are set as co-chairs of the starry gathering that will raise funds to support industry members who benefit from MPTF’s charitable programs and services.

Abendzeitung

AZ: Mrs Blanchett, at the beginning Lydia Tár seems sympathetic. In the end she is almost a monster. Do you understand this woman?

CATE BLANCHETT: I don’t think in those categories, do I love the character or not, do I find her attractive or not? She faces a huge challenge. The film works like a Rorschach test, teeming with innuendo, but no confirmation of what one suspects. The world we live in is monstrous, it supports and invites monstrous behavior and even rewards it.AZ: So to call this woman a monster would be too simplistic.

CB: She is an enigma, a genius, a fantasy. Music is her passion, that’s how I understood her, I knew what she could lose if she lost her position as conductor. I hope the audience can connect with her. “Tár” is a very complex film with many levels.AZ: Do you think many people in the arts are particularly isolated and lonely?

CB: I wouldn’t generalize. Everyone works differently. I also sometimes need quiet and a retreat to recharge my batteries. Nobody can disturb me there. But then I’m happy again to meet a lot of people on the set. Humans are social beings, so contact with others is vital. Creativity can be quite stressful. You have to find a balance between the two extremes.AZ: But this woman doesn’t find it.

CB: Those who are obsessed with perfection often push themselves to their personal limits. Lydia is always fast, runs through life. She has a particularly difficult job as a conductor. There are still different standards than for conductors. The world of classical music is patriarchal. That’s why it has to be disciplined, so controlled, so practical. In terms of energy, no one can keep up with that for long. With all this pressure, you’re just waiting in the film for this volcano to erupt, explode.AZ: In the film you are married to a German concertmaster, played by Nina Hoss. Did you know each other before?

CB: Only fleeting. But I’ve admired her work for a long time. It’s funny that we were both on stage as “Lotte” in “Groß und Klein” in different ensembles. We then also spent a lot of time together and had open conversations, we are connected by a kind of soul mate. Nina is a miracle for me, as she always uses new possibilities. She is a master of her craft.AZ: What was your first reaction to the script? Todd Field wrote it for you.

CB: I devoured it. It’s not about sympathy or easy solutions. Nobody is good, nobody is completely innocent, nobody is just bad. “Tár” is a very differentiated view of institutional power, but also a very human film because the character at the center is in an existential crisis.AZ: And abused their power.

CB: Power does not reside only with those at the top. There is a whole power structure in a team, in an orchestra, in an institution. When my husband and I took over the Sydney Theatre Company in 2008, we carefully built trust and didn’t appear authoritarian. In such a position you have to feel part of the ensemble and convey that. Leading an organization requires a sense of responsibility and sensitivity, a great deal of strength and energy. You have to take care of so much that is not related to the artistic activity. All in all, a thankless task.AZ: Which can feed on you…

CB: And how! Many people are afraid to leave their comfort zone. Lydia knows: If you stay in your comfort zone, that means mercilessly mediocrity. A terrible idea. But she fights and fights, nothing is good enough for her in rehearsals, she wants the best. And so she keeps rehearsing until it meets her requirements. This obsession with perfection prevails in ballet as well as in classical music. Despite everything, we must never lose respect for one another, we must watch out for our own bad habits and should not be brutal with ourselves. Maybe we should think why am I so hard? Maybe there is a portion of your own fear behind it. Perfection can also serve as a shield.AZ: Was this role particularly difficult?

CB: It was the biggest challenge, especially mentally. She totally absorbed me, I could hardly concentrate on anything else. And I can’t get rid of them that quickly either, something sticks. I’ve been thinking about this character for a long time and very intensely, and I’m still thinking about her. It’s tiring, but roles like this help me move forward. That’s why I love my job.AZ: Do you listen to music differently now?

CB: In any case. When I was in high school, I was invited to a friend’s house and was amazed that it was so quiet. All you could hear was the tick-tock of the clock. I learned that you shouldn’t use music as background music, you have to give it your full attention. When I put on a record now, I don’t move from the spot. I think I hear the instruments very differently because I really get involved with the music.AZ: How did you prepare for conducting?

CB: I watched documentaries about different conductors. One gesticulates like crazy, the other jumps wildly around on the podium, the third moves very calmly. This allowed me to find my own style. Conducting is characterized by very individual communication. Training with conductor and coach Natalie Murray Beale was a great help.AZ: And the conducting itself?

CB: I conducted the Dresden Philharmonic in rehearsals for Gustav Mahler’s 5th Symphony. Of course, when the camera rolled, I was already shaking inside. It was fascinating and terrifying at the same time. But we made it together. And I felt a lot of patience and forbearance from the musicians.AZ: You received an award for “Tár” at the US Critics’ Awards and took the opportunity to offer a fundamental criticism of award ceremonies. Don’t like prices?

CB: It wasn’t about that. It’s nice that we’re getting back together after the pandemic and celebrating success together. And I enjoy some awards. But I resist playing off each other as competitors. The press is always keen on a catfight. And that’s far from me.

TAG 24

Cate Blanchett says she inhaled Todd Field’s script. She describes the character of Lydia as her most challenging role: “I was totally absorbed by it. It completely consumed me.” This was also due to the psychological aspects of the story, in which nobody is completely good or completely innocent.

Director Field had explained his project to Nina Hoss in a Zoom conversation. Hoss: “I immediately noticed how intense and clever what he had written is. There’s no question: it was a project that you wanted to be involved in.” She discovered a lot in the material and found it fascinating how complex everything is. “The world, but also Lydia and Sharon’s relationship. Playing this with Cate has been a phenomenal journey!”

Her colleague, Hoss, praises her in the highest tones: “Cate is an actress who can and wants to immerse herself, who is searching and daring. But she doesn’t play for herself, she perceives her partners, is courteous and generous – that’s what makes it very exciting.”

She always asked herself: What’s next, what do we do now? Something happens every minute. “Our kiss in the first scene together wasn’t in the script, we basically improvised. It certainly helped that we both also act, so we had a level on which we understood each other.”

Blanchett says she’s a fan of classical music. Music is a big inspiration for her. The actress: “Music helped me understand all the practical things I needed to learn about how to communicate with an orchestra.”

But she also makes it clear: “It’s not a film about conducting. It’s about an artist who is at the top of her profession.” Blanchett found it terrifying to do all the music scenes first due to the disrupted shooting schedule due to the pandemic: “I would have been happy to have had more time.”

And yet the Dresden Philharmonic, which doubles the fictional Berlin orchestra in the film, became a part of her: “These extraordinary musicians, whom I was allowed to conduct, were deeply generous.” The collaboration was exciting, says Blanchett. “Thrilling,” she says.

Unfortunately, she hasn’t had any direct contact with the musicians since the Dresden shoot. What she regrets: “For me it feels like it was yesterday, not 120 years ago.”

After this experience, Cate Blanchett, for example, listens to music differently today. She explains it like this: As a 15-year-old student, she had lunch with a friend whose father was an opera critic. “And it was quiet. You could hear the clock,” says Blanchett. When asked about this, he said: “You deal with music, you can’t hear it in the background.” Now when she puts on a record, she sits there and listens to it for hours and hours.

“I’m hearing things now that I wouldn’t have noticed before.” She also learned that from “Tár”: “It’s both a blessing and a curse, this gift for conductors to hear things that normal people can’t hear.”

Blanchett was influenced for her role by personal experiences. She and her husband were the artistic directors and managing directors of Australia’s Sydney Theater Company. “We have 250 employees and program around 19 shows a year.”

That is an enormous responsibility: “So I have a feeling for how lonely and isolated you can feel when you have to separate business and art.” Something similar is seen in the power that Lydia has and exercises.

The fact that the film tells the story of a woman who heads the Berlin Philharmonic clearly makes “Tár” a fairy tale for Blanchett. Such positions did not previously exist for women. But that is not the main thing. The film examines how such a prominent position as that of chief conductor corrupts the person performing it.

Blanchett: “The desk is the power, not the person standing on it.” In this case, it is a woman who takes advantage of her artistic position in an authoritarian manner. Blanchett doesn’t think about whether her character is likeable: “It’s not my job to like my character or not.”

In conversation with Todd Field and Cate Blanchett

What has surprised you most about the way people have responded to TÁR, now it has been released?

Cate Blanchett: One of the most rewarding things for me is encountering people I’m not related to saying they’ve seen the film three times. It’s like they’ve been emotionally shocked by it, and then they’ve gone back to try and intellectually process it. Which I never anticipated. I mean, certainly it was a very dense and dangerous experience making it, but how that experience has translated to audiences has superseded all my expectations. What about you, Todd?

Todd Field: I feel similarly. We had a screening a little while ago and the person moderating the discussion afterwards asked the audience, “How many of you have seen the film before?” And nearly half the hands shot up. Then he said, “Okay, how many times have you seen it?” One person said, “Nine times.”

Blanchett: That’s deeply concerning [laughs].

Field: But actually I’ve heard that number more than once!

Does it worry you at all to know some people are delving that deeply into your film, in terms of how intensely they might be scrutinising it?

Field: It’s a fair question. But, having been a projectionist in a second-run movie house, running six projectors every night during high school, I saw lots of movies hundreds of times. And the ones that engaged me, I know every cut of those pictures. So I don’t think it’s unusual. I think that occasionally a film activates something in a person where you can look at it more than once. But I never thought I was making a film that people would watch over repeat viewings like this.

Blanchett: It’s interesting you mention knowing all the cuts in those films that you’ve imbibed over and over, because TÁR is so exquisitely edited. The work you did with Monika was extraordinary. For a film about music, it has a rhythmic quality. I felt that on the first read of the screenplay — it made rhythmic sense.

Field: But I think it’s also obviously a testament to Cate’s artistry. There’s a reason that people are wondering about this character, and if she’s real. And that’s because Cate so utterly disappears within her skin. When Monika and I sat down to start cutting this, the very first scene with Lydia Tár and [The New Yorker staff writer] Adam Gopnik, within three minutes Cate had disappeared. And the problem was, we started to believe Lydia was real, too. It felt like we were cutting a documentary. So we really had to think, “Are we giving this real, living human being a fair shake? Are we being too kind or too cruel to her?” That was a tricky balance to contemplate.

How was that dilemma for you, Cate, as the person embodying this complex, problematic character? Do you have to sympathise with someone to play them effectively?

Blanchett: It’s not for me to judge a character. I’m not interested in that. I think you have to understand the circumstances and the atmospheres they find themselves in. For me, it quickly became clear that something was broiling within Lydia. You don’t know exactly what until you peel back the layers of the story-onion. What’s been interesting about the conversation that’s emanated from her personal crisis is that Todd, in almost an imperceptible way, has been able to weave in these questions of really vast moment.

That single person’s crisis comes to represent somehow a collective societal crisis. Once you reach, as Lydia has, a certain position of authority and power, how can you continue to evolve? Without wanting to sound too highfalutin, we’re asking ourselves that in the societies in which we live. How can we start again? How do we undo these toxic situations that we’ve found ourselves in?

The film has attracted some controversy. Were you anticipating the criticisms TÀR has received, with regard to its perspective on cancel culture and depiction of a woman as an abuser?

Field: Yeah. Our hope was that there would be a very lively discussion, informed by where people were coming from in their own lives, and that perhaps there would be some kind of ability in that debate for people to see things differently, in terms of expanding their own ideas and their own points of view. That’s a fairly high-flown goal for a movie, but we just wanted there to be a potent conversation, and it not just be a shrug or indifference about it.

Blanchett: The conversation was everything, as it was in the process of making it. I do think this is a film that will stand the test of time. And I don’t say that flippantly. I’m not trying to sell you a car [laughs]. But you have to be conscious of the time in which the film is first seen by a public. So all of that discourse is incredibly hot. People have identified their tribes, and the way they respond to anything has to fit into that tribal language. So that was absolutely to be expected. But there are very few places to have public, open, nuanced discourse about these huge things that are happening to us all collectively. When I was growing up, cinema, theatre, performing arts… The foyers of those places and the bars you rolled on to were the places that you started to try and pick that stuff apart. So… We knew it was going to be interesting!

When you first met more than a decade ago to discuss a different film, what did you see in each other that would eventually make this collaboration possible?

Blanchett: Obviously I knew Todd’s work, so that was a huge magnet. And then it was just the quality of conversation. I felt Todd was somebody I could talk to about anything. And he asks really interesting questions.

Field: Oh my goodness, Cate. Wow. [Laughs]

Blanchett: You do! Does that feel like it’s a lie?

Field: I don’t know, but it sounds wonderful. Can you tell my family what you just said? But that meeting was really important for me, because what Cate and I were talking about was another fascinating character — who was the creation of Joan Didion — in a script we had written together [political thriller As It Happens]. And we thought only of Cate for that role, even though I’d never met her. Cate and I sat down in New York and had a very long conversation. The way she talked about the film made me think I was talking to another great filmmaker who just happens to be one of the greatest actors who has ever lived. And who also is really one of the great intellectuals of our time…

Blanchett: [Blows a raspberry] Can you do my eulogy? [Laughs] It’s in my contract somewhere…

Field: [Laughs] All kidding aside, I’m not trying to be hyperbolic. I’m giving it to you straight, you know? I left that meeting so activated and so excited we would be making this film together that, unfortunately, never came to be. So it’s not for nothing that I thought about Cate when I started writing TÁR. But I wasn’t thinking about Cate because of her skill as an actor — I was thinking about the impression I was left with after that meeting, and what it would be like to be in dialogue with her and lock arms and make a film together. It was a nerve-wracking thing, because when I finished writing the script, of course she knew nothing about it. We hadn’t spoken in 10 years. I was really frightened she was going to say no, because there was no backup plan.

Blanchett: The thing is, when you get a call saying, “Todd Field’s written a script, which he’s going to direct,” in your mind you’ve already said yes. So then you open the script shaking, because you wonder what you’ve gotten yourself into. And this was a character that was… She’s beyond a character, in a way. She certainly stripped me bare.

What was the toughest scene to shoot, and how did you work together to get through it?

Field: By design, we were going to be doing all the conducting stuff at the end of the schedule. But we got told fairly late that it was going to be moved up front, because that was the only time we had available with the orchestra.

Blanchett: I had said to Todd, “I’m very slow. Maybe we could start [the shoot] with a couple of long shots of me walking by the camera for the first day. I’d really appreciate it.” He said, “Absolutely.” And then he called and said, “Here’s the thing, we’re gonna lose the orchestra.”

Field: That was really something, because we had to throw everything at that collectively. Because we had a very limited amount of time with this orchestra, there were challenges for Florian [Hoffmeister] in terms of lighting, and we had 95 camera set-ups the very first day; the camera has to be in a very specific place to where Cate is pointing for the tremolo, or where she’s pointing to the horns, or the contrabasses. There were challenges in terms of the sound team, and [costume designer] Bina Daigeler in terms of wardrobe changes with 100-plus people…

Blanchett: Also the orchestra themselves only had limited availability to rehearse.

Field: And we were asking them to not be a band for hire, and to actually perform as characters in significant supporting roles. But also Cate had to just jump off the cliff, and hopefully the wings she had grown were gonna work on the way down. And they did. It was remarkable.

Blanchett: For me, just from an emotional perspective, I viscerally understood what it felt like to be at the epicentre of that sound. So I knew the stakes for the character. But it was a strange gift, in a way. After that, there were so many technical and logistical things happening, like losing locations and constantly having to change, that I don’t think either of us slept at all. It felt like we were in this fever dream for the rest of the shoot. But it did feel like we’d hit the ground running: “If we can surmount that, then let’s just set the bar higher here and make the risk of falling and failure even greater!” [Laughs] That’s why it was so exhilarating. Just the experience of making it… I said it to you the other night, Todd [at the London Film Critics’ Circle Awards]: “I’ll be stalking you from here to eternity, but this particular moment will never happen again.”

Do you plan to work together again?

Blanchett: Todd is a very secretive soul. I’ve made it blatantly clear that I’d love to work with him again. But yes, it’s interesting you ask that question. Um, Todd?

Field: I’ve got something cookin’ [laughs].

Blanchett: That’s all you’ll get. That’s all I’ll get… For another 10 years.

Field: Cate says that, but I’m gonna be just as nervous the next time I go to her. It’ll be the same thing. We’ll see. I’ll be lucky if I get to dance with her again.

Welcome to Cate Blanchett Fan, your prime resource for all things Cate Blanchett. Here you'll find all the latest news, pictures and information. You may know the Academy Award Winner from movies such as Elizabeth, Blue Jasmine, Carol, The Aviator, Lord of The Rings, Thor: Ragnarok, among many others. We hope you enjoy your stay and have fun!

Welcome to Cate Blanchett Fan, your prime resource for all things Cate Blanchett. Here you'll find all the latest news, pictures and information. You may know the Academy Award Winner from movies such as Elizabeth, Blue Jasmine, Carol, The Aviator, Lord of The Rings, Thor: Ragnarok, among many others. We hope you enjoy your stay and have fun!

Black Bag (202?)

Black Bag (202?) Father Mother Brother Sister (2024)

Father Mother Brother Sister (2024) Disclaimer (2024)

Disclaimer (2024) Rumours (2024)

Rumours (2024) Borderlands (2024)

Borderlands (2024) The New Boy (2023)

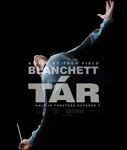

The New Boy (2023) TÁR (2022)

TÁR (2022) Guillermo Del Toro’s Pinocchio (2022)

Guillermo Del Toro’s Pinocchio (2022) Documentary Now!: Two Hairdressers in Bagglyport (2022)

Documentary Now!: Two Hairdressers in Bagglyport (2022)