Happy Friday, everyone!

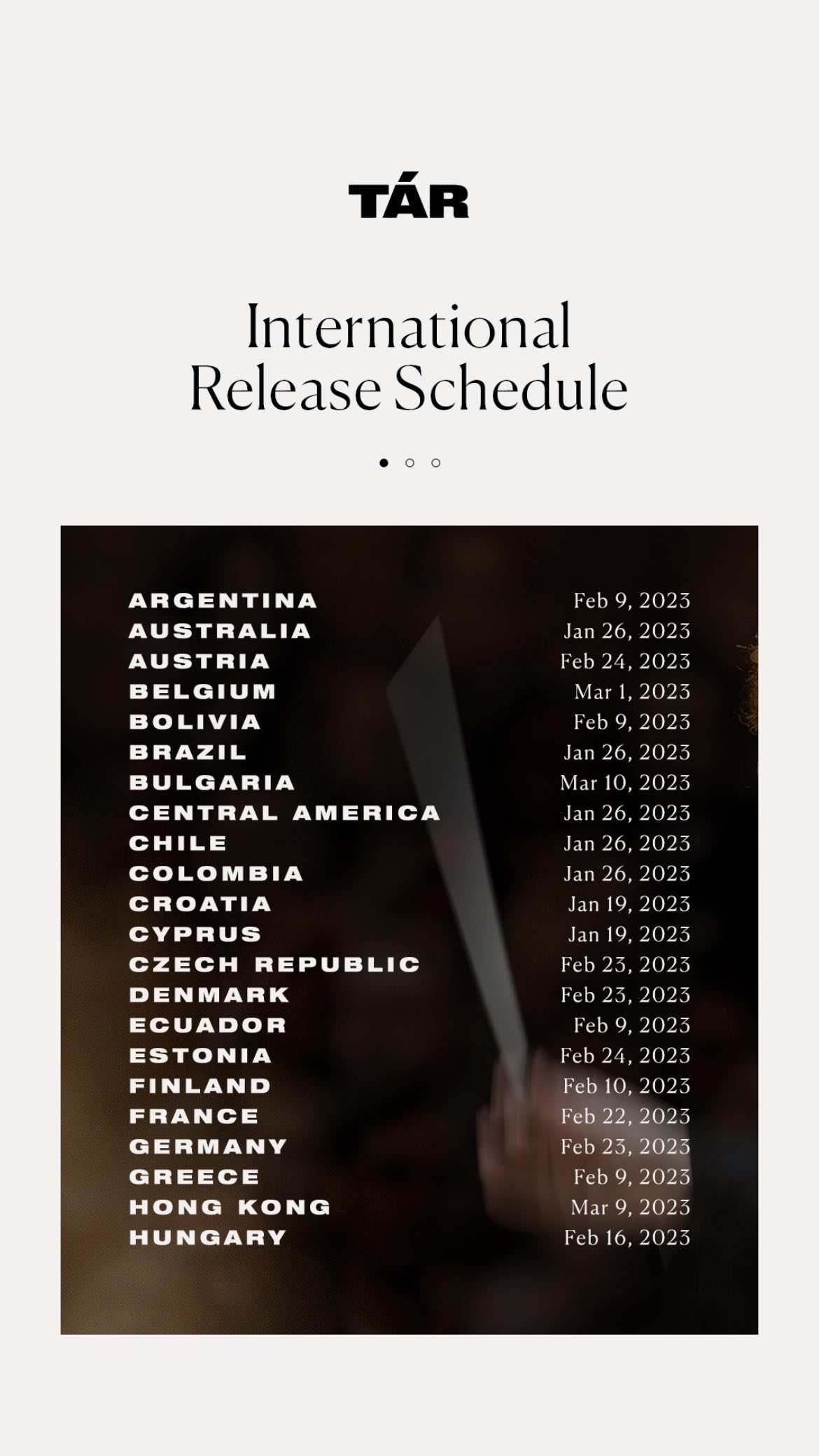

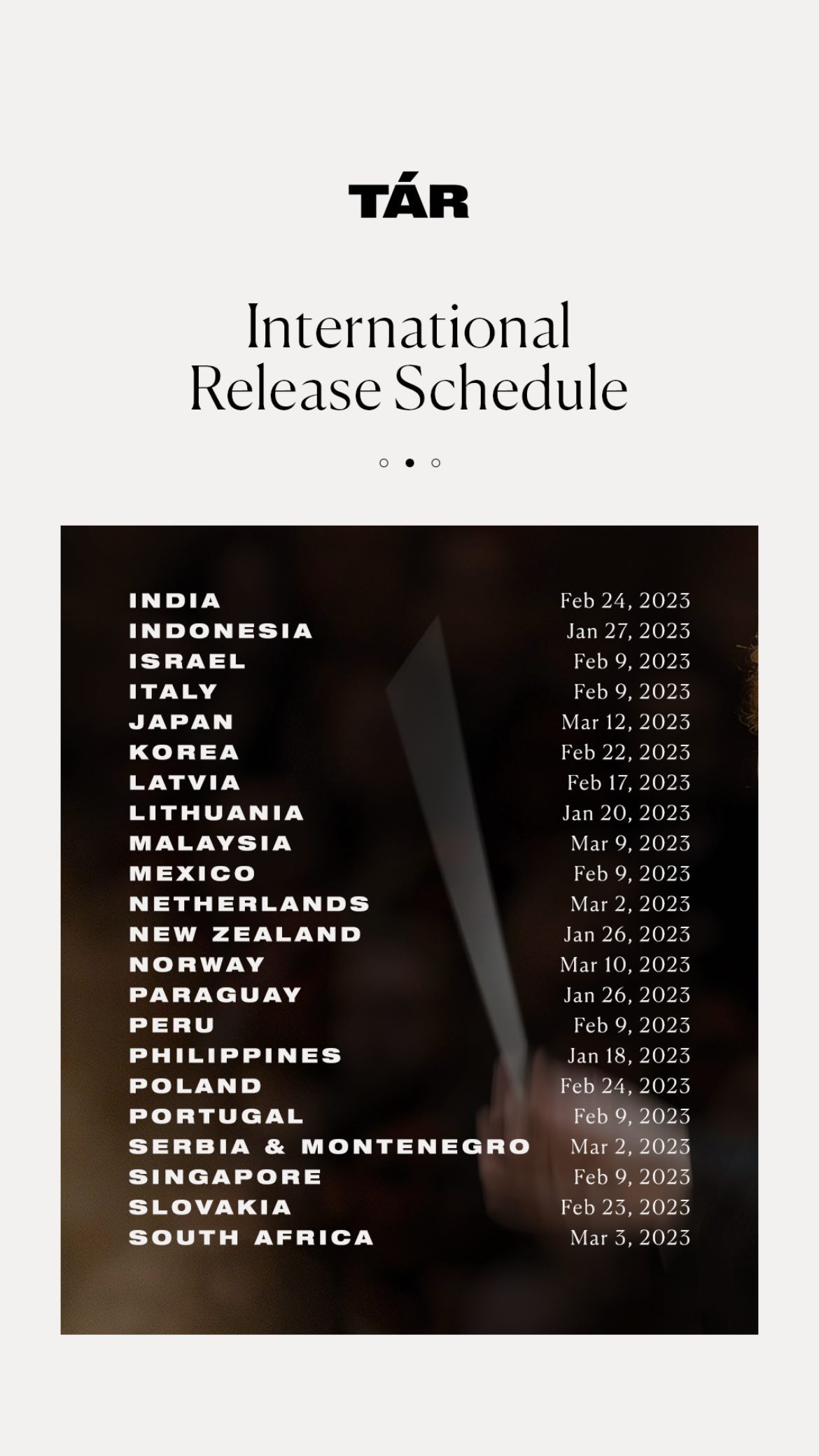

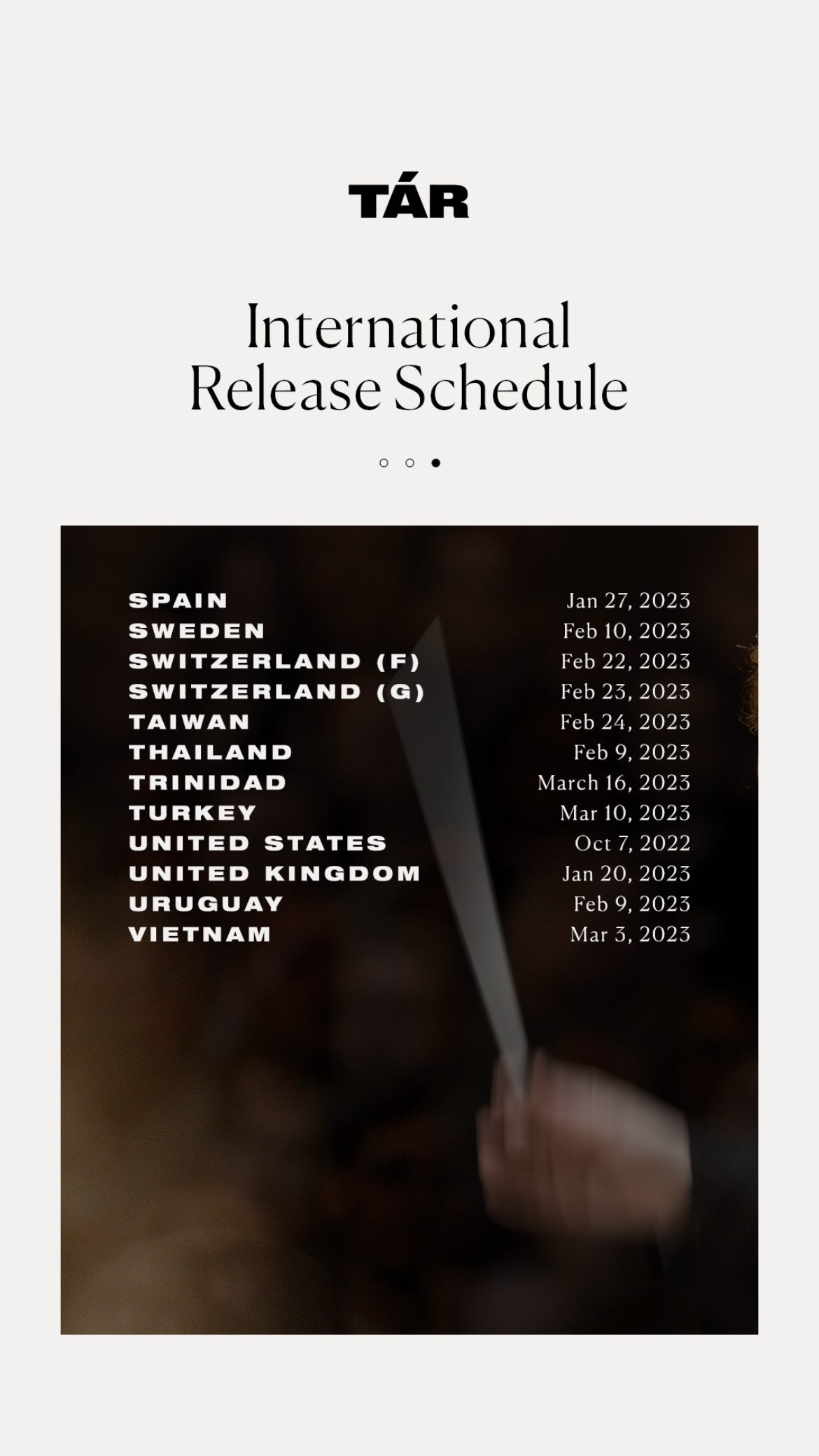

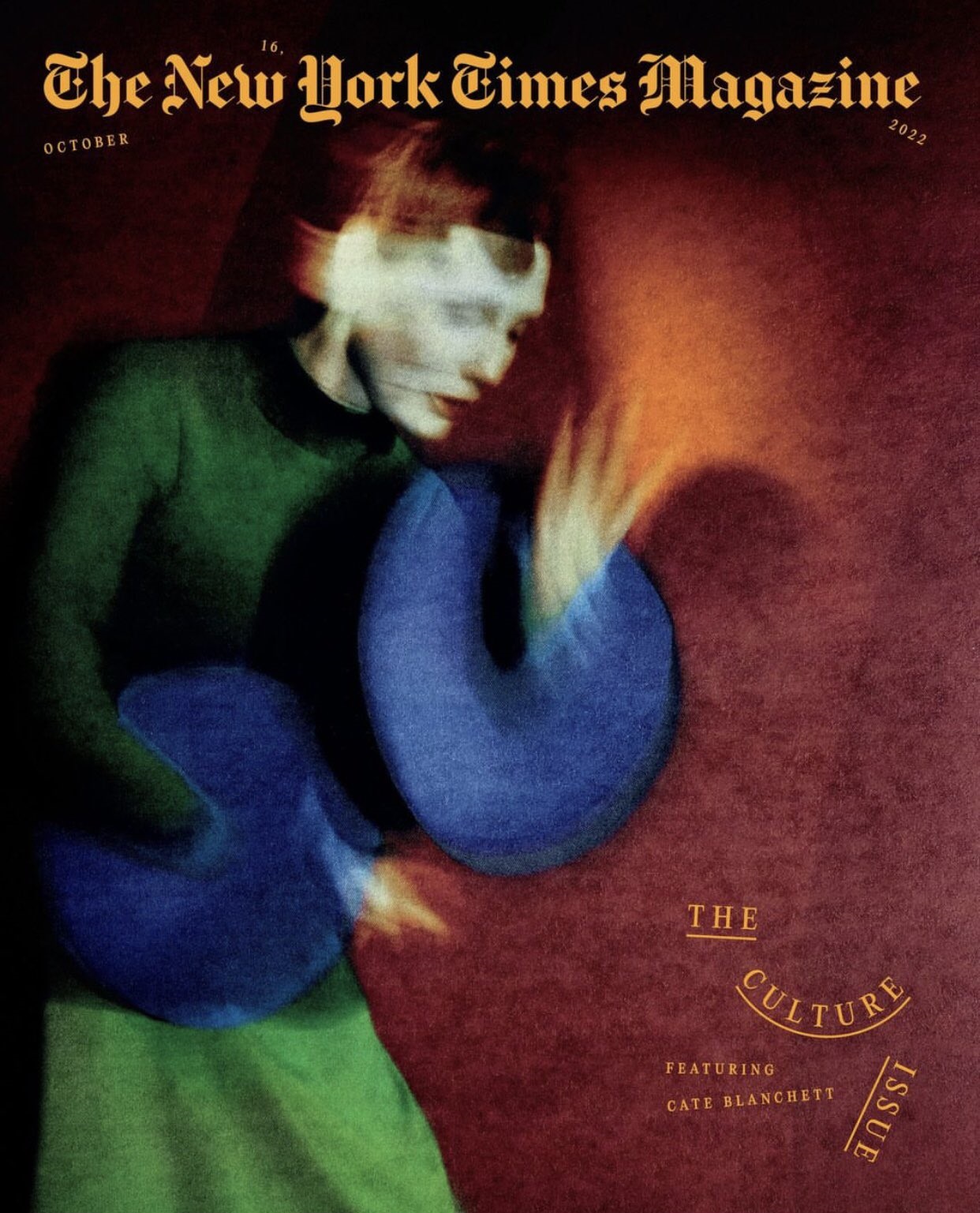

Cate Blanchett covers the Culture Issue of The New York Times Magazine, she talks about TÁR and her other upcoming projects. More interviews has been released these past days, and an exclusive clip from the movie was released by Focus Features. TÁR expands to 30 more theatres today in the US so go see the movie in cinemas near you. You can check the international release dates below.

You can watch the video of when Cate presented the Visionary Award to Giorgio Armani at Sustainable Fashion Awards in Milan few weeks ago.

"Brilliant and implosive." – Indiewire

TÁR is now playing in select theaters. Get your tickets now: https://t.co/DPHDJ9fqlp. pic.twitter.com/VWR1uH09QV

— TÁR (@tarmovie) October 9, 2022

The Elusive Power of Cate Blanchett

Cate Blanchett is accustomed to looking the camera dead on. Hers is the kind of face that inspires directors to tight framing — gleaming, as if smoothed from marble, and yet somehow pliant, changeful. But on the occasions she has sat for an artist, she has noticed a curious pattern: “They paint me looking away,” she told the podcaster Sam Fragoso in February. “When that happens once, you go, oh. When it happens twice, when it happens three times, you think, why am I looking away?” Blanchett saw in this gesture a “not wanting to be captured” and a shade of the self-protectiveness she had to overcome as a young actor. “You have to allow yourself to be seen, and some people have the gift of being comfortable with that really early on. I was not,” she said. “I still struggle with it.”

Maybe for that reason, the breathtaking vulnerability of which Blanchett is capable on film retains a subtle inscrutability. Even in moments of raw emotional exposure, something of the person onscreen remains out of reach — some depth that is sensed rather than seen. “I don’t know how to describe it,” Sarah Paulson, who has worked with Blanchett three times, told me on a call. “She’s almost like mercury rolling on a table, you know? It’s entirely elusive, and yet right there in front of you. And constantly moving and shape-shifting and … and something one would covet. You want to touch that mercury.” “You just want to watch her face almost in repose and feel something elemental coming through that almost translucence,” says Todd Haynes, who directed her in “I’m Not There” and “Carol.” Anthony Minghella, who directed her in “The Talented Mr. Ripley,” once described her as “the Bach of acting.”

At 53, Blanchett has enjoyed just about every professional, artistic and material success a stage and film actress could hope for. She has won nearly every award there is: two Academy Awards, three BAFTAs, three Golden Globes, the Volpi Cup twice at the Venice Film Festival, an honorary César Award, the Chaplin Award. The best directors in the world want to work with her, or want to tell you how life-changing it was to work with her. She has done Broadway and the West End. Alongside her husband of 25 years, the writer-director Andrew Upton, she has run the Sydney Theater Company in her home country, Australia. She’s a face of Armani Beauty. She’s a good-will ambassador for the United Nations refugee agency. She has also retained the freedom to do weirder, smaller indie projects, like the short film “Red,” by the artist Del Kathryn Barton, in which she plays a female redback spider orgasming and then killing her mate, as female redback spiders do.

But Blanchett doesn’t watch her own work if she can avoid it. She dislikes talking about whether a role incorporates any part of herself. She is, she insists, the least entertaining subject, at least to herself. “I’m not interested in any way in a one-to-one direct comparison, or having a moment of personal catharsis in public,” she told me. “Like, ‘Oh the role meant this to me,’ or, ‘I channeled my own inner’ — no.” She looked briefly nauseated. “None of that stuff.”

Unlike many actors of her stature, she has stubbornly confounded efforts to typecast her. Think of her Bob Dylan rendition, papery and emaciated, folded like a grasshopper, shoulders up, mouth closing slowly over itself to wet the bottom lip, cigarette dangling, hand trembling. Or her newly coronated Queen Elizabeth I, ramrod straight with that horse-girl hair and that royal-girl temper. Or her Phyllis Schlafly, serpentine and tweedy, slightly sour about the mouth. She has played women and men; gossamer brides and suited lesbians; the elven sorceress and the wicked stepmother; the 19th-century rancher and the Cold War-era Russian intelligence agent. In “Coffee and Cigarettes,” she did a scene opposite herself. After a series of family films and blockbusters (“Ocean’s 8,” “Thor: Ragnarok,” “The House With a Clock in Its Walls”), she went to London to do a Martin Crimp play about sadomasochism, domination and gender that was so explicit that an older woman in the audience reportedly fainted.

More than anything else, her oeuvre gives the sense of an artist insisting on a person’s right to change, from role to role and from moment to moment. One near-universal principle of acting training is that the performer know, above all, what her character wants. When I asked Blanchett what she wanted at this moment in her life and career, she resisted the question, finding it constraining. In 2010, she did a production of “Uncle Vanya” with the Hungarian director Tamás Ascher, who told her that it was all right not to know what a character wants. “He said that Chekhovian women are like the weather. They change. They’re constantly changing and shifting and moving through things. And that’s why they’re so dynamic and so exciting. And so I thought: I don’t have to answer that question. Because by answering that question, I’m pinning it down, pinning. Trying to pin the character down and say: That’s who she is. That’s what she’s after. Because we’re not like that.”

In her latest film, “Tár,” written and directed by Todd Field, Blanchett plays Lydia Tár, a virtuosic conductor at the peak of her career and at the precipice of a downfall. It’s as intimate and sustained a character study as Blanchett has ever taken on: “Tár” is more than two and a half hours long, and she is onscreen for nearly every frame. The character is a kind of culmination of her interest in the mutability of the individual: Tár is a person with an obscured personal history, a consummate performer whose finely tuned sense of where power lies in any room makes her adept at shifting her own aspect to suit. One senses an instability at her center: Her core self — if there is such a thing — isn’t truly known to anyone, not even her. Frame by frame, “Tár” gives Blanchett as much change, as much weather to move through, as she has ever had.

The first time we hear Tár speak in the film, she is before an audience at the New Yorker Festival, “in conversation” with Adam Gopnik, who plays himself. It’s present day in a world meant to resemble reality in every way: Tár and Gopnik mention the pandemic, and the movie later refers to James Levine, the real-life former conductor of the Metropolitan Opera in New York, who was fired after accusations of sexual misconduct surfaced. Tár, in contrast to Levine, is at the height of her career, a cultural luminary of the type The New Yorker might court. She is the conductor of one of the most acclaimed orchestras in the world and a maestro who has fashioned herself after the historic greats and intends to be counted among them. Her suits are bespoke. Her hair is wild on the podium.

Tár reveres Gustav Mahler and has made a project of recording all his symphonies. The film tracks her preparations to record his Symphony No.5, as well as Edward Elgar’s Cello Concerto in E minor, a career pinnacle. But as the plot spools out, it becomes clear that the recording will never happen. Having forged her image in the pattern of the Great Men, she has also cultivated other now-familiar traits of that type: ruthlessness in the pursuit of glory; a taste for female underlings; an irritation with the rising generation’s desire to revise the canon; a willingness to manipulate the resources of an institution to shield oneself; a perhaps-unwise sense of infallibility.

Field’s choice of orchestral conducting as Tár’s vocation was canny. There is something almost supernatural about an orchestral conductor’s job: They command sound. Their hands can make a theater thunder or shimmer. This is the kind of power that Tár seems to relish. “Time is the thing,” Tár tells Gopnik. “You cannot start without me. I start the clock.” Her hands hover in the air, as if she’s before an orchestra. “Sometimes my second hand stops, which means that time stops.” Her brilliance is evident, her charisma absolute. The film is a close portrait of the way these qualities, which have brought Tár to the top of her world, also make her a kind of monster.

Blanchett was fascinated by the character of Tár as a study of an artist whose pursuit of transcendence and power is both successful and ugly. “How much is permissible when you’re striving for excellence?” she asked. What can a person in Tár’s situation get away with? What should be accepted as the price of her talent? Dishonesty? Sexual indiscretion? Abuse of subordinates? Unpopular opinions? Blanchett was interested, too, in the threshold the character navigates: Tár “is about to go through a massive transition. She’s about to turn 50. She’s found a way to escape herself and to become larger than herself, and better, and bigger than herself in the making of music. But now it’s like that connection has been broken.”

“Tár” isn’t Blanchett’s first time inhabiting an unpleasant person — nor an artist, nor a character who complicates our understanding of femininity and performance. In recent years, she has done a string of roles that play with masculinity (the Bob Dylan homage; Lou in “Ocean’s 8”; the male characters in “Manifesto”) or highlight the fact that femininity can be both a weapon and a liability. Her Phyllis Schlafly is loathsome but almost sympathetic, an anti-feminist whose political career of fighting to keep women in the home is driven by her own need for professional power. Her title role in “Carol” is the totemic midcentury housewife in furs, gleaming curls under a crescent hat, ideal except for her habit of getting involved with other women — her ongoing refusal to be as “perfect” a woman as she looks.

Still, “Tár” is a thorny project even by Blanchett’s standards, one that wanders into conversations that tend to run hot: the whiteness and colonialism of classical music; the possibility of free consent between a mentor and a mentee, or teacher and student; whether an artist’s work can be separated from her conduct; whether one can be a great artist without being greatly destructive or extractive as well.

To prepare, which Blanchett did mostly on nights and weekends because she was shooting other projects during the day, she learned to play the piano, to speak German, to do her own stunt driving. She became versed in the history of orchestral music and the personal styles and biographies of the famous conductors of the past century. Most improbable, she learned to conduct an orchestra, a physical task for which most people train for years. (In terms of its complexity, conducting is comparable to dancing and doing calculus at the same time.) “She showed up on set, and she had memorized the entire script as if it were a play,” Field told me. “I’ve never heard of that. I’ve never spoken to anyone that’s ever heard of that. It’s like learning ‘Hamlet.’ It’s almost impossible to describe.”

The performance that results is assured, mercurial and physical. Something about the way Blanchett’s body occupies the frame feels familiar but hard to place, and then you recognize that posture with which the white male heads of institutions move through the spaces where they work: genial, totally at ease, dangerous. But there are cracks in the self-assurance, seen in the horror with which she reacts to the clicking of a pen, or the breath she needs to take before she touches the piano key. “Tár” can be a difficult viewing experience, especially for those resistant to extended consideration of the psychology and humanity of a person who is brilliant but also a predator. (News coverage and real life afford plenty of opportunities for that exercise.) But Blanchett infuses a recognizable character type with so much unpredictability and self-estrangement that the movie takes on the volatile feeling of a thriller. She is both the shadow and the person running from it.

The home that Blanchett grew up in was silent a lot of the time. Her father died suddenly when she was 10, and after that, her mother had to work long hours. Blanchett has clear memories of her mother putting on a record so they could dance together, but “there was a lot of stuff that was difficult to unpack,” she said. “And it was hard to talk about. So we didn’t. We tried to, you know. It was no one’s fault, but it was often quite quiet.” This didn’t suit Blanchett, who was intrepid and energetic by nature. She would enact elaborate fantasies, usually at the provocation of her sister, like asking strangers for help finding a lost dog she never had. As a teenager, she went through a punk phase and shaved her head. She left the University of Melbourne for a year, traveling by herself through Europe and part of North Africa.

Later, Blanchett went to Australia’s National Institute of Dramatic Art. One attraction of theater was its joyful noise. Rehearsal rooms were full of the best kinds of mess, a clamor of people “talking about things and ideas, you know, and having arguments, and people were crying in the corner, and then people laughing hysterically. But we’re all talking about it until it all blew over and we came back together. And then we’d have another big conversation.” This remains her bliss — the honesty and mess of rehearsal, its perfect impoliteness.

This came to mind when I drove out to Blanchett’s home, an expansive Victorian manor in the English countryside. The Saturday I arrived, there was a cheerful chaos: Blanchett greeted me in a sweater with food spilled on it, apologizing that they were running behind because it was a two-birthday-party weekend (she has four children) and they had run out to buy presents. One teenage son was wandering around the kitchen in his pajamas complaining jovially about an absence of good snacks, while Upton threw together a lunch of bacon-wrapped sausages and fried rice “to keep the children at bay.” I was tasked with making a salad, while Blanchett searched the refrigerator looking for cheeses to put on a board. “I’m literally chucking things into bowls,” she said, amused. “I wish we could put on some kind of fancy spread, which we’d pretend we’d cooked ourselves.”

Upton made a noise as if to say, “Whatever,” and Blanchett shrugged. “Next time. You can say we did,” she said, grinning at me. Then she pointed at her son’s pajamas and added, “Along with the fact that he’s wearing a suit.” Her mother, June, popped into the kitchen to see about lunch. There was a lot of merry cross talk.

We sat down to eat on a covered veranda just through double doors from the kitchen, passing the sausages and salad back and forth. In regular conversation, Blanchett was voluble, but when I asked a question that sounded as if I were interviewing her, she deflected attention onto Upton or the children, one of whom was doing a series of impressive gymnastics maneuvers on the lawn. After lunch, we wandered into her living room, and she sat on the floor, assisting with a complex coloring project. We veered from talking about rewilding efforts in local ecosystems to last fall’s threatened Hollywood crew strike to swimming, which she loves.

“Are you a water sign?” I asked, half-seriously.

“NO!” she said, her eyes going wide. “I had my chart done years ago. I am Taurus, Taurus, Taurus. I am a triple Taurus. Isn’t that … ,” she paused for dramatic effect, “depressing?” She burst out laughing. “Can you imagine Andrew’s — it’s not my fault, darling!”

He laughed. “I like Taurus, Taurus — ”

“What’s wrong with Taurus, Taurus, Taurus?” I wanted to know.

Upton guessed: “Stubborn, stubborn, stubborn?” The zodiac sign Taurus is associated with the bull — grounded, hard-working and occasionally ornery.

“Some would say,” Blanchett replied winsomely.

I joked that this would explain why every single person I had yet interviewed about Blanchett made a point of telling me that she was the hardest-working person they’d met.

“Yes, well, I can add my voice to that chorus,” Upton said.

Blanchett looked suddenly distraught. “That is not — that is — ”

“No, no,” Upton began to reassure her. “Hard-working in a good way.”

“I mean — do you — Spike Milligan had on his grave, ‘I told you I was ill’ — what am I going to have on mine? ‘The hardest-working person’?” She had begun to laugh, face-planting into the rug. “That’s so depressing! ‘She worked so hard.’”

I pointed out that this wasn’t the only thing people had praised her for, which was true. Blanchett is said to be funny, easy and warm on sets. Noémie Merlant, who plays Tár’s assistant, talked about how Blanchett would dance between takes and make the orchestra laugh, even though it was a grueling, nerve-racking shooting day for her most of all. There are similar stories about her clowning to rally spirits on the set of “Mrs. America.” “There is a kind of weightlessness about her when she’s working,” Sarah Paulson told me. “It’s an incongruity when you measure it against her power as a performer. I don’t ever experience her gripping the work or the character or the task at hand very tightly. It feels like she’s holding it loosely.”

Still, her work ethic is legend. Nearly everyone ever interviewed about working with her mentions her preparedness, her focus, her rigor. “She is nonstop,” says Nina Hoss, who plays Tár’s wife, the concert master of the philharmonic. “Preparing. For everything. Thinking about the parts, making her choices there, really practicing, practicing, practicing, concerning the conducting and the piano pieces.”

Blanchett keeps an intimidating schedule. This summer, in addition to postproduction and publicity, she was also spending her days commuting two hours each way from her home to London to shoot a television project with Alfonso Cuarón. After wrapping that project, she would do the festivals tour for “Tár” and fly to Australia to shoot a movie she’s co-producing, “The New Boy,” about an Indigenous orphan who becomes the ward of a “renegade nun,” whom she would play. And she’s developing a series of other projects, including a stage adaptation of the Lucy Ellmann novel “Ducks, Newburyport” with the director Katie Mitchell. (“Ducks, Newburyport” is a monumental undertaking: a thousand-page stream-of-consciousness novel about motherhood, domestic labor, climate change and mortality. “Cate is just up for the impossible,” Mitchell told me.) And there’s a second episode of the comedy series “Documentary Now!” And she has a climate-change podcast with Audible that’s rolling into a second season. And —

“How do you — rest?” I asked, hesitating. “Do you rest?”

She looked at me wearily. “No, I haven’t. And sorry for being … vague. I haven’t been sleeping.” Her kids were on summer holiday; she was preoccupied with the Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade; generally the world seemed to be “tilting off its axis.” She rubbed her forehead lightly. “When do I sleep? No.” She laughed. The next day, she would have a day off, and she had organized a trip to a site where environmentalists were working on restoring the Scottish ground bee’s habitat. I thought again of what Paulson said about mercury, which is bizarrely hard to recover once it’s spilled. Not only does mercury appear to elude touch, slipping right off a surface without leaving a trace; it’s nearly impossible to get it to stop moving.

Blanchett often says she wants things to simplify, to slow down. She sometimes talks about vanishing — quitting acting, disappearing from the public eye. Maybe she’ll learn to make cheese. Maybe she’ll get more serious about keeping bees. She already has beekeeper veils in her attic. (They were a gift from Richard Linklater.) Blanchett told me that as you age, you lose the ability to escape yourself. “You calcify,” she said, not looking thrilled. For an actor, especially one who tries to disappear herself into roles, this can be a liability.

On the other hand, age and confrontation with the self can bring true mastery. She described seeing Mikhail Baryshnikov dance late in his career. She recalled that he wore black pants and a black turtleneck so that his face and hands caught the light, seeming to float. “You were watching the articulation with his hands, and the movement of the dance through his face, and still you felt he had leapt 17 feet into the air.” Her face lit up, and her eyes closed. Her hands moved near her face. “All within a finger’s gesture. But he didn’t arrive at that at the age of 17. It took a lifetime of dance to be able to wear that turtleneck and express it in a fingertip.”

She thought for a moment. “You know,” she said, “I think it’s that the quest keeps going. It’s just the expression of it changes.”

Between our first and second encounters, I received two notes from Blanchett through her publicist. The first was a photo of two dozen or so white plastic rods sticking out of a patch of dirt in a meadow. It was the monitoring site of the Scottish ground bee.

The second arrived a few days before we were scheduled to talk in August. It was a snatch of the poem “In the Coastal Town,” by Kirmen Uribe, that was published last year in The Paris Review. She had found it relevant to “Tár” and wanted to make sure I saw it before we spoke.

The mild summer night.

Music from the bar.

I want to flee into my insides.

I feel the merciful drug

moving into my veins.

Going, going,

because that snake knows

my darkest corners best.

It’s the one thing

that embraces me from inside.

At last I’m calm.I have to admit I wasn’t completely sure what to make of this. I read it a few times and tracked down the whole poem, which on its face is about teenage masculinity and addiction in Spain.

Blanchett logged on to our call from her home office. It was 10 p.m. there, and she had recently returned from a long day of shooting the Alfonso Cuarón project in London. She warned me that her 7-year-old was under the desk, somewhat put out that her mother had to interrupt the night with a work call. “If you hear a rustling,” Blanchett said, “it’s not a rat or a hamster. It’s her.”

When I asked about the poem, her face went blank. After a pause, she said: “Oh, that’s right, I sent you — what did I send you? Hang on.” She seemed to rack her brain. I read her the name of the poet and the title of the poem, but she still couldn’t remember it. “At the time, it must have expressed everything. And now I can’t even remember it. Isn’t that telling?”

I offered to read it back to her. She listened carefully and then nodded solemnly. “Yeah. That does express Tár. Well-found.” I burst out laughing. She grinned. “Good job, me!”

I opened my mouth to ask what resonated with her in this poem, and she sighed and cut me off. “Can we not just let that speak for itself? Do I have to talk about it? This is the problem I have. It’s the eternal problem where you make a deep, instinctual connection with something — and that doesn’t mean it bypasses your intellect — but then you move through it, you put it out there, not for your own enjoyment but for an audience, and then we go through this process where somehow the person that it’s moved through has to make sense of it.”

She might have preferred to be a dancer, to have performed with choreographers like Pina Bausch and Martha Graham, because with dance, “it’s all there, it’s all expressed and it bypasses language.” Not that Bausch and Graham didn’t speak beautifully about their work, not that dance isn’t a kind of rhythmic language, and not that language isn’t rhythmic, for that matter. Language had syncopation, language could make rhythmic sense, the Greeks knew that, and of course there are people who can use language to describe what artists do, she said — certainly Uta Hagen and Michael Chekhov could describe what actors do. “But I … cannot. And maybe it’s also — maybe I don’t want to. Maybe that’s why I sent it to you. I thought: That’ll do. Then I won’t have to talk about it.”

This was an obstacle we ran into a few times in our conversations: her desire not to put language to what happens when she’s acting, or to dissect what she has done after the fact. She insists that she has no process — she just arrives to the stage or the camera with exhaustive research behind her and trusts that something will happen. This seems less like dodging or false modesty than like a desire to protect a way of working that she herself understands to be delicate. Her admiration for Martha Graham is telling here: She believed that the artist is a vehicle as much as an architect, and that the process whereby art is delivered from the universe through the artist is steeped in mystery. Trying to hold tightly to the thing — much less explain it to others — can destroy it.

Lately, Blanchett told me, she had been feeling “a massive urge to be quiet.” She was concerned that anything she might say about herself or about “Tár” would muddle the audience reaction to the film, which felt like a transformative experience for her. “Something moved through us all collectively. And I don’t know what that is, and I don’t want to tell an audience what it is, but I know it’s something.” She promised me she wasn’t trying to obfuscate.

“I feel like it’s a genuine quest that I’m on, which I don’t fully understand myself. But there’s something that I connect with on a deep level with the character Lydia. Not that I’m at all like her.” The look of anxiety and near-nausea returned. “But she seems to be at the end of a cycle. She’s completing this lifelong quest or ambition to match the classical greats, to match Mahler, to leave a legacy. You know, to prove to those bullies in primary school that she is someone and that she can break through those ceilings and realize her full potential. And when you get to that point as an artist, as a human being, you have to risk exploding it all and leaving it behind.”

She described the artist as a person climbing a mountain peak in the hope of reaching something at the top — who then realizes, as she nears her goal, that all along she has been chasing a chimera. The real prize is on the next mountain, which may itself simply be illusory, “constructed by what you thought you wanted, or an external sense of what a peak was,” but which nevertheless now demands her energies. “I didn’t even know I was thinking about it, but it, just, all of this stuff came up, you know. It drew a lot of things together for me.” The movie was about many things, she hedged, but this was a strand of what had drawn her to it, some recognition of the path Tár was on. “Just that sense of continual sense of risk.”

At the end of our final conversation, I asked — hoping to give her some relief from talking about the project of performance and the burdens of age — what’s delighting her right now, what ideas or wishes or artworks are keeping her company mentally. Her voice changed. “Gosh. I’m quite — ” she stopped. “Tired.” The tone of her voice shifted so suddenly, twisted to the forlorn so dramatically, that I grew alarmed. But she was just having trouble conjuring an answer to the question. It had been a long day, and now it was 11 o’clock: She was tired. What was on her mind? Learning to surf. The journalism of Anne Applebaum. Growing things in her garden. A slim novel called “Assembly,” by Natasha Brown. She paused. “You know what I’d love to do, too? I’d love to go for a really, really long walk.”

“How long?”

“Not one of those where I’m going to buy a pack of cigarettes and never come back — ” and we were laughing again. “Not that kind of walk.”

The thing about a long walk is it’s an experience of process, of being in the corridor between the place you started and the place you will eventually be. “It’s like that moment of suspension in dance when you don’t know whether the dancer is taking off or about to land,” Blanchett said. She gestured with her body, as if she were going to take wing and hover. “That moment, that intake of breath before the words come out or the music comes out.” She smiled. “I want to be there. I want to be permanently there.”

Interviews

ODDA Magazine

Cate was in conversation with Elizabeth Banks, who is one of the covers of ODDA Magazine’s latest issue.

CNMI Sustainable Fashion Awards

Paris Match No 3827

Harper’s Bazaar UK behind the scene and outtake

Harper’s Bazaar UK behind the scene and outtake

Source: NY Times

Welcome to Cate Blanchett Fan, your prime resource for all things Cate Blanchett. Here you'll find all the latest news, pictures and information. You may know the Academy Award Winner from movies such as Elizabeth, Blue Jasmine, Carol, The Aviator, Lord of The Rings, Thor: Ragnarok, among many others. We hope you enjoy your stay and have fun!

Welcome to Cate Blanchett Fan, your prime resource for all things Cate Blanchett. Here you'll find all the latest news, pictures and information. You may know the Academy Award Winner from movies such as Elizabeth, Blue Jasmine, Carol, The Aviator, Lord of The Rings, Thor: Ragnarok, among many others. We hope you enjoy your stay and have fun!

Black Bag (202?)

Black Bag (202?) Father Mother Brother Sister (2024)

Father Mother Brother Sister (2024) Disclaimer (2024)

Disclaimer (2024) Rumours (2024)

Rumours (2024) Borderlands (2024)

Borderlands (2024) The New Boy (2023)

The New Boy (2023) TÁR (2022)

TÁR (2022) Guillermo Del Toro’s Pinocchio (2022)

Guillermo Del Toro’s Pinocchio (2022) Documentary Now!: Two Hairdressers in Bagglyport (2022)

Documentary Now!: Two Hairdressers in Bagglyport (2022)