Warwick Thornton’s The New Boy is now in cinemas across Australia. There is a 22-minute extended interview with Cate Blanchett and Warwick Thornton.

Thank you to Kelly for their donation to the site. If you’d like to support the site and make a donation you can click the donation button below this post.

The story of The New Boy will resonate everywhere but it’s a very special feeling to be sharing it in Australia, where it was made with such love and care. pic.twitter.com/j1O8UjwFAF

— Dirty Films (@dirtyfilms) July 7, 2023

Filmink

They’re in town to talk up The New Boy, their first film together, a collaboration that came out of lockdown. “The pandemic happened,” recalls Blanchett, “and one asks oneself, ‘Gosh, if it all ended tomorrow, or in six months, who would I want to work with? Who would I want to spend time with? Who would I want to be in conversation with? Where do I want to be?’”

At the time, she and her husband Andrew Upton “were really homesick” and felt the urge to do something back in Australia for their production company Dirty Films. Blanchett knew Thornton through mutual friends, and they began talking. The filmmaker behind such beguiling indigenous stories as Samson and Delilah and Sweet Country, Thornton mentioned he had a script that he’d written long ago, “a thorn in your paw” as Blanchett puts it. “We found it really mysterious and knew that there was something really special in there that we didn’t quite understand. But we knew it was a document from which you could make an amazing film. And so, we just kept talking about it.”

“[As an Aboriginal], we have lots of different spiritual connections, creators, all that sort of stuff,” he says. “It empowers me every day, wakes me up. It makes me feel special. I don’t understand organised religion. I mean, the corporate version of this, where there is a right…I don’t understand that stuff. So, I will spend the rest of my life looking for signs and having a great time with spirituality and believing and waiting for all my beautiful friends who died to visit me from the other side. They never do. But still waiting. And one day, I’ll die, and I’ll get an answer. And until then, I don’t really want an answer. Because I’m so happy.”

Unquestionably, it’s a relief to see a film about Catholicism that doesn’t involve physical or sexual abuse of youngsters. “Well, you do expect it,” admits Blanchett. “You see a white nun, and an indigenous child and think ‘Ah.’ You can’t help but make assumptions. Not unfounded assumptions. But I think it’s interesting. This film, having percolated with Warwick for so long… time has kind of made it manifest in a different way perhaps than [he] would have imagined eighteen years ago.”

By all accounts, the script for The New Boy has been through quite a transition over the years. “It used to be about a priest and a boy,” explains Thornton. “I’d always say if I walk past a cinema, and I’ve seen that poster – a film by Warwick Thornton – there’s no fucking way I’d go see that! He was actually a nice, confused priest, asked more questions about his own faith. Was still looking for answers. But that version was quite black-and-white. Right, wrong, all that kind of stuff. Bringing in Cate and converting the gender roles created this beautiful shade of grey for the whole film with no real black-and-white. It complicated the film in a beautiful way.”

As Blanchett notes, Sister Eileen “is quite spiritually lost” in her life. “So, I think it makes for an interesting dynamic with the new boy who was also outside. He’s off country. He’s a child. He doesn’t know what his abilities or capabilities or what his destiny is. And so, when he gets dropped in, she’s at the point where she’s prepared to be open to it. Andrew was saying, ‘It’s so interesting, it’s never discussed but the new boy is just allowed to wander through shirtless. He’s allowed to eat with his feet until he wants to eat with a spoon’. Whereas you see all the other boys… there’s something that she identifies on an unconscious level with him being something unique. But it could also be that she’s slightly hungover!”

Blanchett’s return to shooting in South Australia evoked all sorts of emotions. “It was a real homecoming,” she says. “Maybe it’s sentimental. I shot my very first featurette [1996’s Parklands] in South Australia. I’ve had a long history with South Australia. I performed on stage there too.”

Filming in a remote part of the region, Thornton became “obsessed”, she says, with shooting on a particular hill, near to where the production built the monastery from scratch. Despite the fact that Thornton’s team had to contend with wind turbines spoiling the 1940s vibe, it was an ideal setting. “[It] looked like the middle of nowhere to a white person’s eyes,” the actress adds. “But you walked up to the top of that hill and the vista was incredible.”

While Blanchett wasn’t the only adult on set – Deborah Mailman and Wayne Blair, former collaborators on 2012 film The Sapphires, both feature as two more members of the monastery – she was outnumbered by her younger charges. In total, Thornton cast eight children, dubbing them his “pack of wolves”. “Every single scene, they would surprise me and empower me and just do stuff that I couldn’t mentally see, to be that good every single day,” he says. “And I’ll be exhausted by the end of the day, and then suddenly in the morning, this pack of wolves rocked up!”

So, how did Blanchett cope? “Well, I’ve got four [children at home]! So, it was only twice as many! I must say, I approach a set with trepidation when I know there are going to be children on it, from a duty of care level obviously, but also just knowing, ‘okay, animals and children, there’s going to be massive limitations on what one can do’. Often, filming can be freewheeling and bit chaotic. But they were absolutely extraordinary. I mean, extraordinary! The level of support they showed to Aswan, their discipline, their curiosity, but also, they were so alive to the situations and were really fantastic to play with.”

Blanchett’s youngest child, her 8-year-old daughter Edith, was even on set, playing with Reid and the others. “They were angels!” trills Blanchett. “It’s a film where there’s no father figure, obviously. There’s an absent father, but Warwick was the father figure. And there’s a beautiful photo that I’ve got on my phone, when we had the wrap party – which the children totally took over and they were singing on stage. And Warwick went up and you thanked them all and cried, and they all just ran and hugged him. Something they’d been waiting to do.” Thornton looks moved at the memory. “They all gave me a massive cuddle. And then they proceeded to spend the rest of the night going, ‘You cried!’”

Mamamia

When it came to creating The New Boy, Cate Blanchett told Mamamia she and Warwick Thornton built their professional relationship away from the spotlight and after a while, the Samson and Delilah filmmaker shared with her the story he had secretly been toiling away at for decades.

“There was a desire to work together, but with no particular outcome in mind,” Cate said of what prompted her to make that call. “Our conversations began during COVID, when no one knew if there was an end to it in sight.”

Warwick agreed, saying: “We didn’t know if it was the beginning of the end, would we ever work again?”

“So it was quite a great place to start a creative conversation,” Cate continued. “Because it meant there were no cameras involved, it was just an old-fashioned telephone call. We started out talking about childhood stuff and then after a while, you just pulled out this script you’d been working on for a long time,” Cate said, turning to Warwick.

“But then you weren’t sure what it meant to you or to anybody else anymore, and you entrusted us to read it.”

Blanchett’s role in the film was originally supposed to be a male one, but after looking at the optics of the film as a whole, Thorton decided this needed to change.

“The movie was originally called Father and the Son, not The New Boy and it was about a priest,” he explained. “But then it became apparent that if you had seen that poster for a movie, it would come with some very dark connotations.

“And we can’t stand out the front of every cinema and tell people ‘no, the movie’s not like that’,” he continued. “Even I don’t want to watch that film. So even though my film is not about that, there are connotations, so we flipped the gender of the main character. Which was a beautiful idea from Cate and her husband, Andrew (Upton, who produced the movie alongside Blanchett).

With a career that spans decades and a slew of industry awards to her name, including two Academy Awards, Blanchett is an actor faced with a sea of projects she can choose to work on and characters she is invited to portray.

When faced with the choice of which film projects she ties herself to, I ask if she’s motivated by fear or by challenge, if at this stage of her career, her motivation really lies in taking on a role unlike anything she has done before.

She shakes her head to say no before I can really finish asking the question, alluding to the fact that there’s never a performance she’s feared.

Instead, she’s looking for something much more specific.

“I know this sounds strange, but for me, the role is always secondary to the conversation,” Cate explained. “I’ve played characters before who have died on page nine, and I did that because I didn’t want to play the lead role. I wanted to play the role I thought would be the most interesting, the one that could add something to the conversation.

“I’ve also always wanted to play a nun,” she continued, explaining why she was drawn to playing Sister Eileen. “My best friend at primary school was Catholic, and I used to go to mass every weekend with her because I was just fascinated by the ritual and what the ritual is hiding.

“You know, there were so many secrets in the Catholic church, obviously not particularly pleasant ones as has come to light. But as a child and as an innocent, I found the ritual fascinating.

“Sister Eileen is not a nun who’s in an easy place and she’s clearly got a problem with alcohol,” Cate continued. “She’s also having a crisis of faith and into that crisis walks a boy with a vibrant and irrepressible magnetic spirituality.

“She thinks that he can reignite her faith and that he has been sent by God. Which is ultimately very misguided.”

When it came to making the film, Thornton and Blanchett has prepared themselves for the remote Australian filming location and a condensed timeline when it came to their shooting schedule.

But what they hadn’t quite factored in was the joyful chaos that would ensue when the younger cast, comprised of Shane McKenzie-Brady, Tyrique Brady, Laiken Beau Woolmington, Kailem Miller, Kyle Miller, Tyzailin Roderick, and Tyler Rockman Spencer, were let loose on a movie set for the first time.

“While we were filming we had biblical plagues, rain, bees, and bushfires,” Thornton said. “All sorts of strange things happened, but that’s all part of the adventure. The most amazing thing about it all was my total naivety that we were about to work with eight children who had never been on set before.

“Then all of a sudden really reality hit,” he laughed. “And this whirlwind of arms and legs arrived in an eight-seater bus, loud and screaming, and then all the blood just drained from my body because I did not prepare myself for this.

“But they were all amazing, they were the most beautiful children.”

“Amy Baker’s production design was also remarkable,” Cate added in about the filming experience. “And we had the blessing of being in one location the whole time. So for the boys it very quickly became their home.

“They all knew which bed they could go and sleep in, and the detail of the art direction was extraordinary,” she continued. “There was a suspension of disbelief they didn’t have to make because it was just where they lived. It became all our of our home very quickly.”

As we near the end of our interview, I ask Blanchett and Thornton to share why they think it’s so important for audiences to see The New Boy in cinemas and support Australian-made films.

In my head, I pictured the many think pieces being churned out in recent years, bemoaning the fact that audiences are more reluctant than ever to see movies on the big screen. Coupled with the fact that a flood of high-budget blockbusters are currently doing the release rounds, I didn’t want to think that movie-goers would somehow miss out on this compelling and beautifully made new film.

But I quickly discovered that when it came to The New Boy “important” was the last way Blanchett and Thornton wanted their movie described.

“Important is always such a loaded word,” Cate said in response to my question. “It makes it sound as if the movie is just going to be good for them.

“It’s a really funny movie and it’s a war movie. It’s also very open-hearted in an unexpected way.

“Of course, this story brings with it the weight of a certain pocket of Australian history. Which always follows us and in a way, as a filmmaker, you always reference this part of Australian history in some way.

“But this movie is by no means a history lesson or a lecture.”

“I promise you there will not be an exam at the end of this movie,” Warrick added.

Welcome to Cate Blanchett Fan, your prime resource for all things Cate Blanchett. Here you'll find all the latest news, pictures and information. You may know the Academy Award Winner from movies such as Elizabeth, Blue Jasmine, Carol, The Aviator, Lord of The Rings, Thor: Ragnarok, among many others. We hope you enjoy your stay and have fun!

Welcome to Cate Blanchett Fan, your prime resource for all things Cate Blanchett. Here you'll find all the latest news, pictures and information. You may know the Academy Award Winner from movies such as Elizabeth, Blue Jasmine, Carol, The Aviator, Lord of The Rings, Thor: Ragnarok, among many others. We hope you enjoy your stay and have fun!

Black Bag (202?)

Black Bag (202?) Father Mother Brother Sister (2024)

Father Mother Brother Sister (2024) Disclaimer (2024)

Disclaimer (2024) Rumours (2024)

Rumours (2024) Borderlands (2024)

Borderlands (2024) The New Boy (2023)

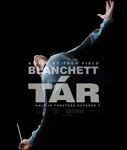

The New Boy (2023) TÁR (2022)

TÁR (2022) Guillermo Del Toro’s Pinocchio (2022)

Guillermo Del Toro’s Pinocchio (2022) Documentary Now!: Two Hairdressers in Bagglyport (2022)

Documentary Now!: Two Hairdressers in Bagglyport (2022)

1 Comment on “Cate Blanchett and Warwick Thorton Extended Interview”

Comments are closed.