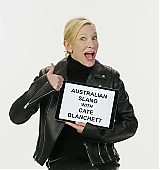

Cate Blanchett covers the February 2023 issue of Vanity Fair Awards Insider plus a video of her teaching Australian slang. She was interviewed by Adam Gopnik for The New Yorker. Cate attended the 95th Oscars Nominees Luncheon, TÁR special screening by conductor Gustavo Dudamel who is the music director at LA Philharmonic, and was on Jimmy Kimmel Live! on Monday. She also attended another Q&A for an all-guild screening of TÁR on Tuesday.

Cate with Noora Niasari spoke to Variety about the Sundance award-winning pic, Shayda.

Vanity Fair

Time tends to stand still in the presence of Cate Blanchett. Martin Scorsese realized as much after spotting her 20 years ago at the Golden Globes. He didn’t know her personally, only her work. But as he watched her stride across the crowded ballroom—her floral dress and statement necklace shimmering—he had an epiphany. Scorsese, who was developing his next film, The Aviator, turned to his wife, only to find that she’d had the epiphany too. “We both looked at each other and said, ‘Katharine Hepburn—there she is,’?” he says.

A few years later, on the set of Todd Haynes’s I’m Not There, in which Blanchett played a renegade mid-60s version of Bob Dylan, Bruce Greenwood had his own memorable sighting, this time in a cavernous warehouse. It had to have been 50 or 60 yards high and four times as long. He wandered the dark space, a little lost, and found some crew gathered around a white light. He saw a striking silhouette of Blanchett, in costume as Dylan, cigarette in hand. Greenwood inched closer as if zooming in on an iconic photograph. “Everybody was as still as she was, transfixed by the stillness that she created,” he says. “And that was my introduction to Cate Blanchett.”

Talk to colleagues about Blanchett, and you hear a lot of stories like this. “She’s like these Renaissance portraits, where the light comes from inside,” says Alejandro G. Iñárritu, who directed her in 2006’s Babel. David Hare, who cast Blanchett in a 1999 London production of his play Plenty, says, “There is no possibility of ever being in a room without knowing if Cate Blanchett is in it.”

I meet Blanchett for lunch on a brisk January afternoon in Beverly Hills. We’d previously said hello at industry events as she made the global rounds for her acclaimed Oscar contender, Tár. (It’s since been nominated for six Oscars, including best picture and best actress for Blanchett.) But here—settling into a corner booth, removing her hot pink spectacles and adjusting a gray scarf—her effect is particularly vivid. Around us, a few diners’ faces angle toward our table. She doesn’t seem to notice; it’s a situation, no doubt, she’s gotten used to.

Tár was written and directed by Todd Field, the Oscar-nominated filmmaker of In the Bedroom and Little Children. It’s his first movie in 16 years, a fact he attributes at least partially to struggles with financing. One project, a script he’d been collaborating on with Joan Didion, brought him into Blanchett’s orbit a decade ago. Field found her unforgettable even after a single dinner. “She has just the most intense wit,” he says. “She will run rings around anyone.” He’d begun thinking about Tár around the same time, and years later, when he received the greenlight from Focus Features, Blanchett popped into his head once more. He didn’t write Tár with her in mind; he wrote it for her, and only her.

Blanchett said yes immediately after reading the script. Due to COVID-induced delays, she had months to prepare—to learn how to conduct, to master the piano, to speak German. (The film is set in Berlin and was largely shot there.) “I was utterly terrified of it. I didn’t know where to start and so I had to just start in an incredibly practical way,” she says. “But because there was so much to do, it meant that there wasn’t any time for nerves.”

The authenticity of the final performance is astounding. Field had tapped the Dresden Philharmonic to stand in for Lydia Tár’s fictional orchestra, and they were only available at the very start of production, meaning that Blanchett needed to jump into the deep end fast. Field had seen her rehearse; he knew she was ready, but even so she fully upended his expectations. “She shows up on a set, she wants to experiment, she wants to be pushed—she wants you to ask her to do things that are 180 degrees from what anyone would think she would possibly do in a moment onscreen,” he says. “How far can I push her out onto a tight wire with no net? It’s one thing to be able to get across. It’s quite another to dance on it or stand on your head.”

Tár is an extraordinarily ambitious woman. She has ascended to the top of her field, honed her craft to a place beyond perfection. As she obsesses over an upcoming live recording of her white whale, Mahler’s Fifth, she arrogantly squashes anything that could get in her way. Yet she is deeply haunted—by her abuses of power that went in tandem with her rise, for one thing, but also by aging and wondering what happens after you confront your white whale. Blanchett’s embodiment feels cellular. She acknowledges something “happened” during filming. She keeps getting tripped up by my questions about this. She’s not being evasive; on the contrary, she’s wildly curious, giving long and thoughtful answers. She’ll stop herself often: “Sorry, I can’t remember, what were you asking me?”

She calls the role “skinless” at one point, the best clue she’ll provide to this intense connection between the portrayer and the portrayed. So what does ambition mean to Blanchett? “It’s something that traditionally is seen as being an unattractive thing for a woman to hold,” she replies quickly. “It’s synonymous with being ruthless.” Then she turns the inquiry on herself—“I look at the things that I choose to take on as ambitious, and that always contains a very strong possibility of monumental, catastrophic failure”—before chewing on it a little more. “I don’t know if I’m an ambitious person or a restless person.” She squints at me and grins. “It’s a very hard question, Dr. Freud.”

Onscreen, Blanchett always holds your attention like there’s nothing else to see: those ferocious monologues in Elizabeth and Blue Jasmine that command complete silence. The immaculate glamour in Carol and Nightmare Alley, masking women of incredible force. The ingeniously screwball take on, yes, Katharine Hepburn in The Aviator, for which she won her first of two Oscars (the second being for Blue Jasmine). Even in noisy blockbusters—the Lord of the Rings trilogy, Thor: Ragnarok, Robin Hood—she pulls off unusual performances. Scorsese noticed this from the moment he became aware of her with 2000’s The Gift. “From movie to movie, she was extraordinarily precise about character, physically, vocally, emotionally,” he says. “She had a kind of magic that harked back to an earlier era in movies.”

From attending drama school in her native Australia to her Hollywood breakout in Elizabeth to her success since, Blanchett has managed a prolific and varied filmography while raising four children with her husband of 25 years, the theater-world veteran Andrew Upton. For every awards-bound prestige movie, there’s a paycheck-delivering tentpole, or perhaps an experimental Aussie project. (Few Hollywood actors know the international cinema scene better.) In person, Blanchett carries it all in a way that swiftly puts you at ease. “She has that Australian thing that’s just like, get in the trenches, do the work, don’t make it hard for anyone else,” says Melanie Lynskey, a New Zealander, who acted opposite Blanchett in Mrs. America and Don’t Look Up. “We don’t really let each other get too full of ourselves. It’s part of the national psyche.”

She’s also funny—like, weird funny. Multiple collaborators describe falling into “giggle fits” with Blanchett. “I’ve never known anything like it—I’ve never giggled so much,” Lynskey says. On Tár, “we had to stop and shut down for 15 minutes because we were having fits together,” Field says. Blanchett certainly knows how to break the ice with her directors. “I once said, ‘I don’t know if we’ve got time to do 15 or 20 takes with you, Cate,’ and she’d be like, ‘Oh, it’s hard enough remembering these ridiculous lines about Asgardian mythology, I think I’ll give you about three good takes,’?” says Taika Waititi, who turned Blanchett into a delicious supervillain for Thor: Ragnarok. “She’s got a really wicked sense of humor, and it’s very fast. But I never felt condescended to. I never felt undermined because she had more experience with bigger directors.”

I feel this too—she asks about my family, my upbringing, my favorite movies, going well beyond the rote small talk between journalist and celebrity. It’s surprising that she shows up on set in the same fashion, knowing how much she puts into her work. In fact, this may explain why she has thought about quitting acting altogether. It can become too much. (Once, when Julia Roberts was talking to her for Interview magazine, Blanchett said, “When I was younger, I would wonder why the older actors I admired kept talking about quitting. Now I realize it’s because they want to maintain a connection to the last shreds of their sanity.”) I assume this is a merely occasional feeling. “It’s not occasional—it’s continual,” Blanchett says. “On a daily or weekly basis, for sure. It’s a love affair, isn’t it? So you do fall in and out of love with it, and you have to be seduced back into it.”

After finishing Tár, Field suggested to Blanchett that she take an acting break. She did not. Alfonso Cuarón had offered her the lead in his upcoming Apple TV+ series—“You have to answer that call,” she says—and she recently coproduced and starred in an Australian film, about an Indigenous orphan who arrives at a remote monastery, that took years to get off the ground. And Tár still lives. Blanchett has been featured in character on a concept album, which is now available on vinyl, containing excerpts from the film as well as original music by composer Hildur Guðnadóttir. Then there’s Field’s anticipated short film that expands on the “Tár universe,” premiering at February’s Berlin International Film Festival. Even now, “Todd and I are on the phone three, four, five times a day, every day,” Blanchett says. The memes treating Lydia Tár as an actual person are, in some ways, real for Blanchett. She can’t seem to let her go.

Blanchett remembers Field’s suggestion: “He said ‘don’t work for a while,’ and I probably should have taken the advice.” She finally has. “I just said no to a couple of things. I think it’s time to be quiet.”

Blanchett swears she is not on social media, not even under an alias, so she needs to be caught up a little. I tell her that there’s an Instagram account called @dykeblanchett that has more than 50,000 followers. Blanchett cheers: “Oh, good!” Then she thinks for a moment: “Only 50,000?” Hey, it’s just a fan account.

Between I’m Not There, Carol, and now Tár—Lydia calls herself a “U-Haul lesbian,” raising a child with her partner, the orchestra’s concertmaster, Sharon (Nina Hoss)—Blanchett has amassed a sizable queer following. Recall the queer comedian Hannah Gadsby joking about Blanchett “hogging all the moody lesbian roles.” Blanchett is aware of this particular fandom, especially as Carol has developed into a gay Christmas classic since its 2015 release. Her being the face of its legacy is undeniable. As Todd Haynes, who directed Carol, puts it for me, “You think of the film, you think of the title—and the extraordinary images of Cate Blanchett.”

Blanchett has said that, in the cases of both Carol and Tár, she “didn’t think about” the fact that she was playing a gay woman. Yet at the time Tár was conceived, few women had led major orchestras, let alone gay women; Lydia occupying this position implies a seismic cultural breakthrough. Her story resembles that of Marin Alsop, the chief conductor of the ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra, who, like Lydia, is a lesbian and was mentored by Leonard Bernstein. (Though there may be some reason to doubt that latter detail in Lydia’s biography.) Alsop acknowledged these “superficial” similarities while criticizing the film’s dark character study in January, telling the British Times, “To have an opportunity to portray a woman in that role and to make her an abuser—for me, that was heartbreaking.”

Blanchett has said she drew from various artists and musicians in creating Tár, and tells me the character is totally fictitious—“a fantasy.” How much did she factor in that she’d be playing a queer person who defied the odds, only to be corrupted by power? “I don’t think about my gender or my sexuality,” she says. “For me in school, it was David Bowie, it was Annie Lennox. There’s always been that sort of gender fluidity.” This echoes the 2015 video installation Manifesto, in which she adopted 13 distinctive personas while delivering pieces of famous polemical speeches, as well as her Bob Dylan in I’m Not There. But I press her on this a bit, and she admits to feeling perplexed by the very notion of having to think about stepping into an identity outside of her own: “I have to really listen very hard when people have an issue with it. I just don’t understand the language they’re speaking, and I need to understand it because you can’t dismiss the obsession with those labels—behind the obsession is something really important. But personally I’ve never had it.”

A crucial early scene in Tár, filmed in one virtuosic take, finds Lydia in a heated argument with her student at Juilliard over separating the art from the artist, the creative value of diversity, and the changing of the canonical guards. The student in question identifies as a “BIPOC pan-gender person,” which visibly rankles Lydia. She berates him until he calls her a bitch and storms out. “That’s what Todd does—there are no answers to these things, but the conversation’s really important,” Blanchett says. She considers Carol: “If it was made now, me not being gay—would I be given public permission to play that role?” I ask if she thinks she should be. “I don’t know the answer to that,” she says.

The topic clearly weighs on Blanchett, as she understands the sensitivity around it—and the potential for saying the wrong thing. “If you and I were having a conversation [25 years ago], it would be in your publication and that was it,” she says. “Now, somehow it’s like these opinions get published, and Scarlett Johansson doesn’t play a role that maybe she was the only person who could play it.” (This likely refers to Johansson, after backlash, exiting a project in which she was to play a transgender man.) She adds, “I don’t want to offend anybody. I don’t want to speak for anybody else.”

Navigating these debates comes with the territory of an Oscar campaign. Blanchett is a strong contender for this year’s Academy Award, and if she wins, she’ll join Meryl Streep, Ingrid Bergman, and Frances McDormand as the only women to have won three acting Oscars. (Katharine Hepburn, naturally, holds the record at four.) Times have changed so fast that none of those stars had to answer questions like these on the trail. Nor did they go on Hot Ones, the popular web talk show, and eat spicy chicken until they cried while promoting their movie. That said, “I asked to be on Hot Ones,” Blanchett says. “I’ve been wanting to go on Hot Ones for years.”

But much of the mechanics of awards season feel frustratingly familiar to Blanchett. “Part of me was really hoping that, out of the pandemic, so many things were going to be done differently,” she says. “Why don’t we have a matriarchal structure, in which…all these things are in dialogue with one another rather than it being a horse race? But of course there’s a lot of vested interest in creating the drama around the drama.”

She remembers hitting the Oscars circuit for the first time in 1998, for Elizabeth, which traced the early years of Queen Elizabeth I’s reign. Blanchett was a newlywed who’d made that historical drama only a year earlier. She went from Venice to Toronto to all of the usual places Oscar contenders have gone for decades. “It was literally like I was dropped on Mars,” Blanchett says. “I didn’t know what anything was. I didn’t know what the roundtables were or what panel conversations were—or anything at all.”

She doesn’t mind answering tough questions, but she answers them in her own way, in her own time. When I ask her about Tár’s disappointing box office, for instance, she keeps talking about sheep’s milk. “We were in Tasmania recently, and we went to this, like, vodka vineyard, and it was made from sheep’s whey,” she says. “And they had coffee with sheep milk and it was really delicious!” I play along, telling her I grew up partly in New Zealand; she yelps, “Speaking of sheep!” We laugh. Our server returns to deliver our drinks and Blanchett tries to keep the bit going, as a few eyes around the dining room shift back in our direction. “Can I ask, do you have sheep’s milk by any chance?” The server checks and eventually reveals they do not, in fact, have sheep’s milk. Blanchett assures her, “I’m totally fine with cow.”

So anyway: box office. Tár has made less than $7 million domestically as of this writing, about half of what Carol—which was produced on a much smaller budget—pulled in. Blanchett waves her hand in defense. “I don’t know,” she says of my framing. “People said that, but it had such a limited release.” She’s right that it opened decently on the handful of New York and LA screens where it initially hit theaters. But the fact is that virtually every art house release in 2022 has met a fraction of the theatrical audience that movies like it would’ve found pre-pandemic. A fraction, in other words, of what movies like Elizabeth and The Aviator and Blue Jasmine needed—movies that ambitious (or restless, depending on your perception) actors like Blanchett have built their careers with, movies that studios justified with the promise of reaching a specific kind of audience.

I wonder aloud if this scares Blanchett. “Being scared of things is sometimes an important part of them—girding your loins to work out what you’re going to do about it,” she says. “I find it concerning for sure.” She admits her aggressive promotion of Tár is partly because the film delivers a richly cinematic experience, from its sound design to its careful cinematography, and she wants people to see it in a movie theater: “The opportunity to be seen by people in the cinemas—those windows are closing up. They are.”

But Blanchett also talks about young people loving Tár more than she ever expected; about discovering one of her favorite repertory cinemas, Row House, in Pittsburgh; and about the beauty of still being able to see Lawrence of Arabia at a theater in Rye, near the English countryside town where she and Upton live. Where is she going with all this? The self-described “rambling” coalesces into an expression of hope for her movie and her character to lead a long life. “I’m going to date myself, but the whole idea of things sitting in repertory so that you can go back and revisit them over time—I do think that this is one of those films,” she says. “It’s rare, but it’s all about time. And it’s going to stand the test of time.”

Toward the end of lunch, our server returns. She informs me and Blanchett that, starting at six o’clock in the evening, sheep’s milk will be available at the restaurant. Blanchett looks simultaneously delighted and mortified. I burst out laughing. This couldn’t have gone any other way. I think back to everything I’d heard about and seen of Blanchett coming into our interview. Iñárritu called her “relentless”; Scorsese, “astonishing.” Lynskey said she was “our greatest actress,” and many agree. Talk about standing the test of time. So when Cate Blanchett raves about sheep’s milk, who are any of us to dismiss it?

“Not just for me, was it?” Blanchett asks with an embarrassed smile.

“For everyone,” the server replies. “We all need to try it.”

Full interview on Vanity Fair

Cate Blanchett interviewed by Adam Gopnik

I met Cate Blanchett in 2021, on the set of Todd Field’s movie “Tár,” in which she was playing Lydia Tár, an apparently formidable orchestra conductor, and I had been cast as a highly scripted and agreeably heightened version of myself. Field had reached out to me months before to say, startlingly, that he had written a movie for Blanchett that also had a character within it bearing my name.

Mostly, though, I was intrigued by the idea of working—even on a pro-am basis—with Cate Blanchett. Like everyone else, I had been watching her in movies for years and had been enthralled by her seemingly limitless gift at impersonation in the elevated, theatrical sense. She’d been effortlessly credible playing any woman, from an elven queen (in the “Lord of the Rings” trilogy) to a disturbed New Yorker (in Woody Allen’s “Blue Jasmine”)—and not just women, come to think of it, since she’d also had a memorable turn as Bob Dylan, in Todd Haynes’s “I’m Not There.” Over the many hours of filming our scene together—a staged interview at a fictional version of the annual New Yorker Festival—I was struck not by Blanchett’s self-evident virtuosity but by her professionalism, which, of course, is the pragmatic form that virtuosity takes. Take after take, she found new things in our very discursive material that somehow added to the whole without ever breaking the continuity of the past take’s work. Meanwhile, in the predictably endless pauses between takes, we conducted a long sotto-voce conversation about Samuel Beckett, Australian theatre, eating in Berlin, and, above all, our children (she has four) and the pleasures and predicaments of raising them.

The other evening, we met for another conversation, at my apartment in New York, for which she’d agreed to play Cate Blanchett while I would continue to play myself. “I was having this sort of inverted stage fright coming,” she told me when she arrived. “It’s like we’re going to rehearse for a scene from a film that we’ve already shot.” But we quickly settled in to talk about listening to music, going before audiences, and the art of acting, seen from both her Olympian height and my Lilliputian lowlands.

This is the most meta occasion that I have ever taken part in. We are redoing, for The New Yorker, a conversation that we simulated in Berlin, pretending to be—

Where you were playing yourself.

Well, I was playing a version of myself. I was playing a part that, in fact, I often play in life, which is . . . the conversationalist, right? But it is a part I play. It is not who I am in any sense. So I was playing that part, but I was also playing myself, as a person in Berlin. So I was playing myself, playing myself, playing myself.

I know. Charlie Kaufman’s going to call.

The first two sentences are my performance. But then you realize that Cate Blanchett is actually giving a performance because she’s playing Lydia, and it’s Lydia who is having difficulty because she is playing herself. That’s Lydia’s predicament: playing herself. Did you have any expectations when Todd Field sent you the script?

No, I don’t know what you felt, but it seemed to arrive fully formed. It’s a bit like “Mork & Mindy.” So, you had to reverse engineer how you got there. And I think that it’s a very challenging film, but ultimately a very rewarding film as a result. Todd’s and my conversations were intensely practical. It was this constantly evolving tsunami of a thing. The process of making it was to try and get as close to the fire as we possibly could and understand what it was, because I think that this erupted out of Todd and that it made complete sense to him on one level. But then he had to deconstruct it in order to actually make it reconstructed.

Todd is not a programmatic artist. He didn’t have an editorial idea that he wanted to execute with this. He had a vision of a particular person navigating her way through the world. Did you feel, when you read it at first, that it didn’t have a program? That it’s genuinely emotionally ambivalent and complex?

And very ambiguous.

Yes.

Maybe that’s what I was trying to say, and I don’t know where you sit as a writer: it’s very hard to not lock down that ambiguity very early on in the process and start to say, “I understand what this is, and I’m going to lean into what I perceive it is,” but allow it to continually evolve and change and grow.

I’ve had it in the theatre. I’ve had a very deep relationship with the director Benedict Andrews. I can see him in my peripheral vision, almost sort of conducting as if I were a silent-movie actress.

And so, [Todd and I], we have this symbiotic relationship. And I can feel that. He’s like Martin Scorsese. He sits not behind the monitor but by the camera. And you can feel the energy. He wouldn’t give line readings, per se, but I could almost feel that I was channelling something through him.

And Todd was not programmatic. He’s also not prescriptive. Normally, when someone has written something as refined and deep and dangerous as the script was when I first read it, you would then think that he would have a scalpel-like approach to the type of performance, which he did not.

Todd has said that he didn’t write it with you as his first choice. He wrote it for you, and if you had not wanted to do it he would not have been able to do it at all. Did you know that when he sent it to you? And what was your first response to the script? Did you hesitate at all?

No, I didn’t hesitate. My agent, Hylda, has known Todd for a long time. And I met Todd ten years ago, when he was working with Joan Didion on a screenplay. I’d obviously seen his films and loved them, and I knew his work as an actor and then discovered he was a musician, so we got on incredibly well. We didn’t stay in contact, but my agent said, “You’ve got to read the script.” And she’s only said that to me one other time, and that was when Todd—the other Todd, Todd Haynes—had sent the script for “I’m Not There.”

I will add that when Todd first got in touch with me, I thought it was Todd Haynes.

So you didn’t know him?

I didn’t. He reached out to me out of the blue and said, “There’s a character in this movie who has your name. Would you be interested in playing him?”

When I read it, I said, “You better call Adam Gopnik.”

Laurence Olivier famously said that he loved to work from the outside in—from costume and makeup and all that. And I was so stunned when we saw images of what you were going to wear. How did you arrive at that? We won’t say the Annie Leibovitz look, but . . .

I watched everyone. It was watching conductors talk about conducting and watching concert musicians and how they presented themselves. And there are many, many documentaries that were hagiographies, really, visual hagiographies that talk about Herbert von Karajan and the persona—

Not to interrupt you, but did you happen to see that beautiful, strange film about Wilhelm Furtwängler and the Third Reich?

Yes, yes, fascinating. All those details, so interesting. But Bina [Daigeler, the costume designer]—we did “Mrs. America” together, and she’s so fantastic. So we talked a lot about it. We started sort of strangely with the hair, because you look at male conductors, and some male conductors talk about distraction on the podium. But what conductors choose to wear or not wear, how to present themselves there, is part of the performance. And they have to walk in as the Maestro. I looked at a lot of male conductors’ relationship to their hair over time.

Like Lenny Bernstein, right?

Yes, exactly. And so then it was also just thinking about: this was somebody who came alive in movement. It’s like when you’re onstage, you have to have the ballet put into a costume, so you can move.

It was also, back to the practical level—they were very long days. So Bina and I talked, we came up with what the silhouette would be, what she wears, and Todd was very, very keen on the baseball cap, so that was kind of a pivotal point. And also being adrift as an American in the classical music of old Europe—talk about a pariah.

I mean, you read a lot about the relationship between von Karajan and Bernstein and this long sort of exchange. Bernstein was never really invited over there [during von Karajan’s tenure]. But I think von Karajan was quite obsessed with him.

They came of age, professionally, at the same moment, right after the war, and von Karajan, who was with the Berlin Philharmonic, famously told his orchestra, “We will make music as you’ve always made music.” And Bernstein is a Jew coming into time when New York was becoming the predominant cultural power.

Yes. It was really, really complicated. All these conversations go into the melting pot. So it made me think a lot about what gives one the right—how many stage hours do you need before you can truly play Blanche, or any of the great roles? Yet these characters are all written in their sort of late twenties, early thirties. Blanche is such a young woman, but she’s such an old soul. That’s the wonderful thing about being in the theatre, that time is such an elastic thing.

I started thinking about [Lydia] not having a mentor. And so who did actually mentor her, and how did she create a sense of an authentic connection back into the music that would give her permission as an American to even get the chance to play this music? Therefore, the construction of self for her was a life raft, and it was quite important to allow the door to remain open.

Yes, exactly. It’s the scaffolding she needs to climb up to the position that she deserves to have. That’s what makes it complicated.

But yet in a visual sense they then needed to give the audience access to her sense of authentic self—even though she’s so estranged from herself and adrift—when she’s in flow, when she’s at the center of that sound.

Martha and I and our son, Luke, went to a screening and watched the movie and your astounding performance. And then we got to the end. As we left, we were having a debate among the three of us, because each of us responded to the very end completely differently. Luke saw it as her vindication: Lydia’s got an orchestra. Whereas I, being a much more conventional person, saw it as a kind of humiliation: she has to do this performance for an audience of cosplayers. And I’m sure that Todd’s intention was the first more than the second, don’t you think? But the beauty of it is the ambiguity of her . . .

Yes, I think it is, because it’s in the name, and she does these anagrams [in the film.]

Once I got to the anagrams, I kept saying, “Tar is such a difficult name. Can you put another ‘R’ on the end of it? It’s Tarr.” I said, “Who’s going to go and see the movie ‘Tar’?” Then I was in Budapest, and the word for “pharmacy”—I had to look it up to pronounce it—it has t-á-r, with an accent. And I took a photo of the “tár” and I said, “Look, at least that gives it some panache.”

Yes. Well, not only panache but you can imagine it gives it a kind of an implicit backstory, right?

Yes.

That Linda as a young girl saw that word in a photograph, or something. . . .

When I saw the anagrams, I was thinking, I can’t play “rat.” He’s so elusive, Todd—wonderfully elusive—but therefore very magnetic and compelling, both as a person and as a filmmaker. He said, “Well, yes, I guess the anagram of ‘Tar’ is ‘Rat.’ I guess it is.” And I said to my husband, “I can’t play that level of judgment. We’ve got to change the name.” And he—my husband—just very simply said, “It’s also an anagram of ‘Art.’ ” I’m so literal, but of course when I first read the ending I was profoundly depressed by it. But then in the performance of it I was utterly liberated.

I had listened to John Mauceri talk about how one of the most difficult things that he’s ever done is having to play to a click track when he does music at the Hollywood level—because you have somebody else’s rhythm and somebody else’s music, and you have to bring it alive. And I thought, I understand that innately as an actor. You’ve got somebody else’s rhythm, particularly when you’re dealing with a new work, which is what a screenplay is, isn’t it? And when someone writes as rhythmically as Todd . . . but, yes, you’ve got to invent something, you’ve got to bring it alive, and you’ve got to throw it all away and make it live with the other actors. So you’re constantly adjusting. I felt, in a way, that it was simply about being at the center of sound, and not having a sense of judgment on what that sound is. It was liberating.

I have to tell you, I was speaking with a wonderful composer who often writes film scores and the ending was the only part of the film he didn’t like, because he thought it was implicitly condescending to movie-score writing, which was the farthest thing . . .

Yes. I don’t know if I told you this, but I had worked for months with Natalie Murray Beale, my friend, who I brought on just to help me with the conducting. I was in Budapest to work out parts of the Mahler. I sort of could read those four or five pages of the score, so I knew exactly what I was talking about. And so I wanted to get the music that would be playing for Monster Hunter. [At the end of the film,] I stand up on the podium. I’d just been moving through the music in my head in silence. But while I was moving through this, in front of the student orchestra, as soon as I lifted my hand the sound started to come, and then they kept going, and so I kept conducting.

Wow.

And then we just kept making this sound together, beyond the part that I had studied.

It was your vindication, your vindication as a conductor.

It was astonishing, because they were leaning in, hungry for direction.

Had you studied piano as a kid? How were your musical skills coming in?

I had. You go and watch Eastern European acting students, and they’ve gone to very expensive academies, and they can all play five instruments and speak seven languages, and they can stand on one hand. And I’m thinking, Well, I speak English, possibly. I played piano as a girl. I played recorder. But what are my skill sets? I kept saying, with every pregnancy, “I’m going to go back and finish my finance degree, and I’m going to pick up the piano.” But it’s a very sad indictment of me. I have to be pushed by a role to go and do that.

I will tell you that I am now thirty-nine years late turning in my Ph.D. thesis.

I think you made up for it.

Well, but not in my family, because all my five brothers and sisters have Ph.D.s except me, so . . .

It’s unfinished business. Competitive unfinished business—even worse.

So, no, it was wonderful to have music come back into my life, because there’s such cacophony in my house. I’ve only been listening to music in a deep way, I think, probably since the pandemic—since a bit of silence came back in, because I had some space in the car.

It was like I was in a floatation pod. I didn’t want a single sound to come into my world. Also, I like vinyl. In a way, albums are like symphonies, put together in an order, because your ear is guided through in a way that completely bypasses the intellect—you can intellectualize it later, but even contemporary music is put together the way an album is produced. It’s so important. The rhythm of it, the sequence of it.

Yes, it’s true, and we lose that.

The shuffle function.

I try and tell our kids about how, when we were growing up, side one and side two of a Beatles album were crucial, and it was crucially different to know what was on side one. Then it came to an end, and you turned it over, and you had a separate experience on side two. And they have no interest in it. But it’s true about the pandemic. It was sort of the last time—or the first time in a long time—that classical music seemed to matter for so many.

I remember at the height of the pandemic, when we all had to Lysol the green beans, that I thought to myself, O.K., every night I’m going to have to Lysol everything we have in the kitchen, so I’m going to listen to Beethoven’s quartets. I’ll finally catch up.

Yes, we were doing very repetitive, monotonous small tasks, so you could really attend. And I think it’s that thing about having these really dense works on as background music. I just can’t do that. I have to sit.

Has it been held over for you from the film to now? I mean, are you carving time just to listen?

Yes, yes.

Oh, that’s fantastic.

And I have to tell you, I had so many moments of pure joy making this film. I’m so reticent to talk about the work of it, because it felt like such a liberation and a freedom, probably in large part because music came closely back to my life. But also being with people en masse, together again—and being in that really dangerous space that I think we so often avoid being in as artists, myself included, but also as humans, between chaos and order—it was so joyous.

Yes, it was a happy set in that way, too.

I don’t think anybody knew on a visceral level that we were making something. Todd and I kept calling it, like, a monster that was locked in the closet. We kept calling it the thing. We never referred to it as a film or a scene. It was the thing.

I remember, in fact, that Todd said to me, when I arrived, “Now we’re going to do the Gopnik.”

The Gopnik, yes.

Language can be an open window, and it can be an island that one swims to, or it can be a homecoming, but sometimes it can be a prison. Maybe that’s why we didn’t talk about it—the thing—too much, because we didn’t want to weight it down.

Or define it.

Because the thing that the audience always is excited by is the question. It’s not the answer.

That’s right.

There are a lot of things that she says that you realize she’s heard—she’s heard Bernstein say that, or somebody else. . . .

In the Juilliard scene . . .

Yes, yes. And there were these little moments where you felt, That’s who she can be. That is her greatness. She doesn’t necessarily see it, because we’re watching her. The audience is a fly on the wall. We know more about Lydia Tár than she knows about herself.

Which is part of her predicament. I was going to say: I was sort of stunned by some of the responses to the film. You’re wise to keep away from it, obviously.

Yes. We have no ownership over it, nor should we. How people define it and lean into it and discuss it is not for us to be involved with in any way.

I deeply believe this to be true. Nonetheless, it is sometimes provoking, because there are things in the film that seem to be so admirable that have been nipped at on occasion, as inevitably happens. One is that the conversation in the film about classical music is élitist or difficult. This seems to me to be the farthest thing in the world from the truth. It’s people who are passionately engaged with their work talking about the work that they do. And that’s part of the joy. It’s like watching “Apollo 13” and saying, “Well, they talk too much about the space program.” That’s the material.

It’s in our moments of passion, whether it be video games or monster trucks or Mahler. That’s when we take flight. That’s when we forget our physical selves, and we commune with the thing. And I suppose I’ve learnt to lean into being more sociable, but I’m inherently quite shy. And I think Todd is as well.

Very.

I’m also grateful that we had this massive thing between us to discuss.

Yes.

We’ve become very good friends as a result, because, by leaning into your passion with other people collectively, you invariably expose parts of yourself unwittingly, both positive and negative.

That’s why I love rehearsal rooms so, because people will bring in the cone of silence. It’s more respectful and, I think, intimate. And so many people have been exposed publicly through the supposed cone of silence of A.A. A lot of stuff gets revealed in a rehearsal room that stays there. It’s very respectful, the ones that I’ve been in.

I was thinking about this when we were working. You’re sort of a theatre-imprinted actor, right?

Creature.

Creature, yes. But that’s still foundational for you—the experience of theatre. I was so struck when we were working together that you would find something new in our exchange each time we redid it, and yet had the discipline to know that it had to be in continuity with everything else you’d been doing for the previous two days.

Yes. I’ve learned to sort of translate the experience that you have from week one to week two to week three, a rehearsal from take one to take two to take three. You go in to try and find something new. I think you’ve got to have a very strong third eye, because you’ve got to slow that bit down, not for internal rhythmic reasons but simply because the camera dolly doesn’t have time to get round there. I can sense that the light is hitting the lens there, and it looks a lot better. So you develop that technical 3-D sense the longer you do it. But the thing that I find—which wasn’t in our scene, because we did have an audience, although they were told where to laugh . . .

So, just to clarify, the audience was told in German where to laugh at the things that we were saying in English.

Yes. But I worked with an actor who has since passed away, a great English actor, and we were on the West End, and he would do this thing—I keep using that word—this technique he had, and the director was getting really cross because he would always get a round [of applause] as he walked off. The director said, “I’ve got to tell him to stop that.” There’s a technique—which I have refused to ever learn—of making people continue to clap at the end.

Right.

And they do it in orchestral music a lot, but you can get around by looking at the audience a certain way. So I knew that that was a skill that Lydia Tár . . .

Would have, yes.

Even though the audience didn’t speak English, they knew when to laugh, because I was giving them the cue. But something I’ve had to learn in the theatre is that I have found curtain call to be an agony.

Really?

Because you’re still coming out of something. It’s like when you go and see friends who have just come off doing a massive gig, and they’re still . . .

They have not yet returned to the other self they play.

Right. It’s my husband’s favorite moment, watching actors just before they go onstage.

That liminal moment.

But I’ve found the exposure of the curtain call—or what seemed to me, as a young actor, the self-aggrandizement of standing up there—to be incredibly difficult.

I worked with a wonderful theatre director, Barrie Kosky, who I was at university with, and he ran the Komische Oper. He’s an amazing pianist, incredible conductor, and amazing director. He’d get really cross with Australian actors about not allowing the audience to have that. He said, “None of that false humility. Stand up there. The applause is for the audience. It is actually not about you. They’ve been sitting there attending to this evening. They complete the circle.”

Full interview on The New Yorker

Academy Awards Nominees Luncheon

#CateBlanchett doesn't walk the carpet… she glides. pic.twitter.com/S1wOQGUAyQ

— KTLA Entertainment (@ktlaENT) February 13, 2023

Best actress nominee Cate Blanchett arrives at the 95th Academy Awards Nominees Luncheon @TheAcademy #Oscars pic.twitter.com/dQuG01tRzZ

— On The Red Carpet (@OnTheRedCarpet) February 13, 2023

No hay suficientes palabras para describir a la reina ? #CateBlanchett ? #Oscars #Oscars95 pic.twitter.com/42M1kAipmx

— TNT™ América Latina (@TNTLA) February 13, 2023

Cate Blanchett, nominated for "Tár," poses for the cameras at the #OscarsLuncheon. https://t.co/7lag8zCGZX pic.twitter.com/5ftRb7Ki70

— Los Angeles Times (@latimes) February 14, 2023

Lead actress nominees Michelle Yeoh and Cate Blanchett greet each other at the #OscarsLuncheon. #EEAAO #Tárhttps://t.co/7lag8zCGZX pic.twitter.com/QawrRdklvg

— Los Angeles Times (@latimes) February 14, 2023

Lydia Tár is here (unless this is just a third-act dream sequence) pic.twitter.com/UITLxW9KYm

— Kyle Buchanan (@kylebuchanan) February 13, 2023

Future Cannes collab? Cate Blanchett is chatting up director Alice Rohrwacher pic.twitter.com/vIr1VOPvrn

— Kyle Buchanan (@kylebuchanan) February 13, 2023

Jimmy Kimmel Live!

Cate Blanchett stopped Jimmy Kimmel Live! to promote TÁR which is in select theatres in the US and available to stream on Peacock.

TÁR special screening moderated by Gustavo Dudamel

Blanchett on what it felt like to face an orchestra for the first time: pic.twitter.com/jjWqHubYO5

— Amrita Khalid (@askhalid) February 14, 2023

@jenoaharlow Todd Field roasting Cate Blanchett after a Tar screening. Please someone tell me the name of that band? Thanks for bringing me @theonlylex

On Monday night at the Academy Museum in Los Angeles, Vanity Fair hosted a conversation between Blanchett, Tár writer-director Todd Field, and powerhouse conductor Gustavo Dudamel, the current music director at the Los Angeles Philharmonic, who recently made headlines by accepting the same role at the New York Philharmonic.

From the start, it was clear that Dudamel was quite taken with Tár and its approach to a world he knows well—he even makes a cameo in the film, glimpsed on one of his album covers. Calling the film “wonderful,” “unique,” and “very credible,” Dudamel told Blanchett, “Your way to conduct, your gesture, is very natural.” In return she joked, “Are you offering me a job?” He didn’t blink: “Absolutely, you can become music director in Los Angeles!”

Later, more seriously, Dudamel asked if Blanchett had any interest in becoming a real conductor. “This is not an interview of that sort!” she said with a laugh. “But no, it was extraordinary…. When we had to prepare on Zoom, our conducting consultant, Natalie Murray Beale, said, ‘Nothing is going to prepare you for the experience of you giving the downbeat, and that sound coming back at you and through you.’ It was an unforgettable, life-changing experience. I mean, you get to do that every day.”

Blanchett and Field repeatedly turned the tables on their interviewer, fascinated by his musical experiences and decorated, nearly 14-year career leading the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

“You have to feel prepared, but you cannot predict what is going to happen,” Dudamel said of his work on the podium. “That is something that you don’t learn in a school of conducting. You learn the factual things, you learn the structure, the interpretation, the history, but no teacher will tell you what is going to happen there. You felt that.” An overarching theme of Tár is the power inherent to being a conductor, something Dudamel says he sensed even as an 11-year-old stepping on to the podium for fun. “For me, conducting is more than leading something; it’s trying to guide people through inspiration,” he said. “When I did my first rehearsal, I was 11 years old, my maestro was late, I was in the violin section, and I went to the podium and started to play-imitate him and other conductors. I was making jokes and all of that. In a moment, everything got pretty serious. I was like, This feels good. Power feels good. It was the most natural thing. I was not prepared for that.”

At a young age, Dudamel made a name for himself by winning the first Gustav Mahler Conducting Competition; like the fictional Lydia Tár, who is preparing to conduct Mahler’s Fifth Symphony, Mahler has loomed large over his career. “I think to interpret a conductor or musician is very complex, because an artist has many layers; also, when you are a conductor, you are interpreting music about other geniuses,” Dudamel said. “Mahler’s Fifth is a symphony that has been part of the history of the 20th and 21st century as one of the most played but one of the most difficult pieces.”

With a laugh, Blanchett joked, “I’m glad you say it’s difficult; I thought it was just me.”

For her part, Blanchett viewed it as the logical fit for the “dangerous place” Lydia is at when it comes to attempting to shape her legacy. “You’ve surmounted so many pinnacles, and she saved this one to last,” she said. “As an artist, when you are avoiding one aspect of the task in front of you, it’s often the thing that is going to unlock a breakthrough. In a way, I kept thinking, Will the breakthrough rerelease her back into the world, back into life? The things that she’s been avoiding in herself. Of course, this symphony is famously about love, and that’s maybe something that I thought: Well, is the character struggling with that? The sense of love in her childhood, the love of another person, the love of the people that she’s working with. And so it sort of became a metaphor as well as an incredible piece of music.”

Dudamel couldn’t agree more. “Completely, because it has everything,” he said of the Fifth. “It starts with a funeral march, it has a storm in the second movement. So, in a way, I think that’s the life of Lydia Tár.”

TÁR all-guild screening (Feb 14th 2023)

These were my Valentines today.

Was stoked to moderate an all-guild screening of #TAR with Cate Blanchett and Todd Field today.

An attendee came up to me after the screening and said, "he should make a sequel."

This is how the TÁR Cinematic Universe expanded. #Oscars pic.twitter.com/Ktt4pualK9

— Clayton Davis – Stand with ?? (@ByClaytonDavis) February 15, 2023

Cate Blanchett on the Sundance Award-Winning Shayda’s Powerful Connection With Audiences

It’s a Sunday evening in London in early February and two-time Oscar winner Cate Blanchett is freshly changed from an award show when she logs onto a Zoom with Noora Niasari, the writer and director behind “Shayda,” the powerful Sundance award-winning film executive produced by Dirty Films, the production company co-founded by Blanchett.

“I’m so happy. It’s fantastic. It’s great for Todd [Field], it’s so great for the film,” Blanchett says as she fields congratulations on accepting the London Critics Circle’s best actress prize. “And I just read that Viola Davis became an EGOT!”

The topic of awards is the conversation du jour this time of year because awards are capital in the entertainment business — and Blanchett knows a thing or two about this topic, with eight Oscar nominations to her name. Ultimately, the accolades help a film reach audiences far and wide. In the case of “Shayda,” for example, winning the World Dramatic Competition’s audience elevates the film from an intimate production that might’ve only sparked in Australia to a global platform, especially now that it has a major distributor.

Variety can exclusively announce that, following the film’s successful Sundance debut, Sony Pictures Classics has acquired all media rights in North America, Latin America, Benelux, Eastern Europe, Portugal, the Middle East and Turkey in a deal negotiated with United Talent Agency (The agency also represents Niasari, alongside Granderson Des Rochers, LLP.)

HanWay Films will be selling the remaining international territories and screening “Shayda” to buyers in the upcoming EFM. Metropolitan has come on board as the French distributor. Local distribution in Australia and New Zealand will be handled by Madman Entertainment.

There was a particularly beautiful moment during one of the Salt Lake City screenings, when a woman who worked in women’s refugees in Utah gifted Niasari a hand-knitted scarf.

“She took the scarf and put it over my neck at the end of the screening and thanked me for telling this story,” Niasari recalls. “There was also a young guy who was half-Iranian at the world premiere. He was shaking and still sobbing at the end of the screening; he was so grateful to feel seen and to feel that connection to a film that he hadn’t really felt before. It’s been a very cathartic experience like both for me, for Zar, for my mom and for audiences.”

Blanchett cuts in, asking, “Was your mom there? How did she go with it all?”

“She did so well. She was fielding questions at the Q&A,” Niasari replies. “I really made a point of bringing up all the real-life inspirations to the stage and she loved answering the questions. She was very confident on stage and told me she had the time of her life. By the time we were saying our goodbyes, she was so emotional, and so grateful, and so happy with it.”

“That’s something that’s quite remarkable and brave that you did as a director — you so openly and generously gave of yourself and your personal stories to the actors and to the people that you’re making the film with,” Blanchett notes. “They had access to you and your mother; then, you really trusted them to bring their own points of view to it.”

As a result of Niasari’s “brave and bold” act of exposing her personal history, she explains, the film has a “timeless” aspect to it, connecting this 90’s-set story to conditions in present day.

“That is the power of the film,” Blanchett continues, referencing the woman in Utah who gave Niasari the scarf. “[‘Shayda’] is so culturally specific, and of that time. It is not only the hideous, horrible, horrific events that are now unfolding that make this film more timely and more urgent, but it’s also because, between you and your cast, you’ve created this sense of being a timeless universal struggle. To me, that’s what the audience award really spoke to — that particular connection that you’ve made across time.”

Thanking Blanchett for her kind assessment, Niasari replies: “There’s nothing more that a filmmaker could want than to make that connection across cultures, across time and across all these barriers. What I wanted to do was create a bridge.”

Blanchett and Dirty Films boarded the film thanks to Sheehan, whom Blanchett had worked with on 2005’s “Little Fish.”

“He said you’ve got to see this emerging filmmaker’s work,” Blanchett says of Sheehan’s pitch, before turning to Niasari to praise her directly. “We were blown away by your shorts — the connective tissue between them, but also how visually different they were.”

Then, upon reading the script for “Shayda,” Blanchett was profoundly moved.

“Even though my story is so profoundly different from yours — not only culturally and geographically, and I’m a lot older than you are, but being raised by a single parent, all of those struggles and my relationship to my mother, it brought all of that stuff up,” she explains. “And without, in any way, sentimentalizing that relationship, it spoke to the primacy of [motherhood], and to the quiet heroism, that a lot of women — whether they be born in Tehran, Melbourne, or wherever — there are often invisible struggles that are somehow not brought to the screen in a way where they can connect to a bigger political struggle.”

Blanchett, of course, is referencing the women-led movement in Iran, sparked in last fall, when 22-year-old Mahsa Amini died in police custody, after having been arrested by Tehran’s morality police for wearing a hijab “improperly.” Amini’s death sparked a revolution in Iran, now coined the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement, which Niasari paid tribute to on the red carpet in Park City, wearing a pin bearing the slogan.

Because the film offers Shayda’s — and Niasari’s — domestic experiences as a window into the larger cultural conversation, Blanchett is hopeful that the project will create a bridge toward greater understanding of what this movement is about, as well as the prevalence of the sexual violence that women experience no matter what language they speak or where they’re from.

“When you’re not in direct geographic relationship to the conflicts in a culture that is not your own, you often don’t become fully aware of them until the volcanic eruption happens,” Blanchett says. “What is beautiful about the film is that it allows us to look back slightly back in time [and] it allows us to sort of see the incremental ways that that horrendous abuses of human rights can come about.

She adds: “Films like this, they’re not instructional. It’s heartwarming, heroic and ultimately triumphant. You’re not going there for a history lesson, but it does allow you to quietly reflect.”

Cate’s glam team:

Make-up by Mary Greenwell using Armani Beauty products

Hair by Robert Vetica

Styled by Elizabeth Stewart — Cate in Lanvin (Academy Luncheon), Loewe (Jimmy Kimmel Live!), Moschino (TÁR Screening 1), Stella McCartney (TÁR Screening 2), jewelleries by Louis Vuitton

Sources: Vanity Fair, Variety

A Manual for Cleaning Women (202?)

A Manual for Cleaning Women (202?) Father Mother Brother Sister (2025)

Father Mother Brother Sister (2025)  Black Bag (2025)

Black Bag (2025)  The Seagull (2025)

The Seagull (2025) Bozo Over Roses (2025)

Bozo Over Roses (2025) Disclaimer (2024)

Disclaimer (2024)  Rumours (2024)

Rumours (2024)  Borderlands (2024)

Borderlands (2024)  The New Boy (2023)

The New Boy (2023)