Good day, Cate Blanchett fans!

Cate Blanchett, with Deborah Mailman, made an appearance at this year’s Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts (AACTA) Awards via video. They were on set of Warwick Thornton’s The New Boy which wrapped this week in South Australia.

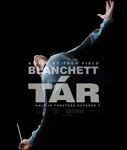

We have added a section on the site where you can see the list of the awards and nominations Cate received for her performance in TÁR — left sidebar of the site (if on desktop) or scroll down if you are using mobile.

Variety released the Actors on Actors conversation with Cate Blanchett and Michelle Yeoh. Various conversations with the cast and crew of TÁR are now available to watch. There is also a new interview from Screen International and we updated the gallery with some stills from the movie and FYC posters.

EDIT: Additional interview from The Times which you can read below.

AACTA & The New Boy

this was the message from cate & deb that was played at the aacta’s last night ? pic.twitter.com/RMbptFB7JG

— zee (@cursedsapphics) December 8, 2022

Conversations and Nominations for TÁR

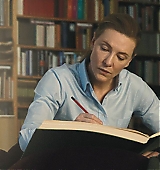

The Franz Liszt Academy of Music shared some photos of Cate when she visited the academy. If you will remember Cate was in Budapest during the second quarter of 2021 for filming of Borderlands that is yet to have a release date. While on break from filming, she was preparing for her role as Lydia Tár. Emese Virág, who is a teacher at Liszt Academy, was Cate’s piano coach.

Emese Virág and Cate Blanchett at Liszt Academy

The 2022 Atlanta Film Critics Circle Awards

Best Lead Actress:

Cate Blanchett – TÁR#AFCC #AFCC2022Awards #TÁR @tarmovie @focusfeatures pic.twitter.com/lH2e4LuoSC— Atlanta Film Critics Circle (@ATLFilmCritics) December 5, 2022

4th DiscussingFilm Critic Awards

BEST ACTRESS:

Taylor Russell, Bones and All

Michelle Yeoh, Everything Everywhere All at Once

Cate Blanchett, Tár

Danielle Deadwyler, Till

Mia Goth, PearlSee the full nominees list: https://t.co/izJK6UYPgb pic.twitter.com/4WDt0e69In

— DiscussingFilm (@DiscussingFilm) December 7, 2022

2022 #SatelliteAwards Nominations

ACTRESS IN A MOTION PICTURE DRAMA

• Jessica Chastain – The Good Nurse

• Cate Blanchett – Tár

• Michelle Williams – The Fabelmans

• Danielle Deadwyler – Till

• Vicky Krieps – Corsage

• Viola Davis – The Woman King pic.twitter.com/zjQjOKdZQF— Satellite™ Awards (@SatelliteAwards) December 8, 2022

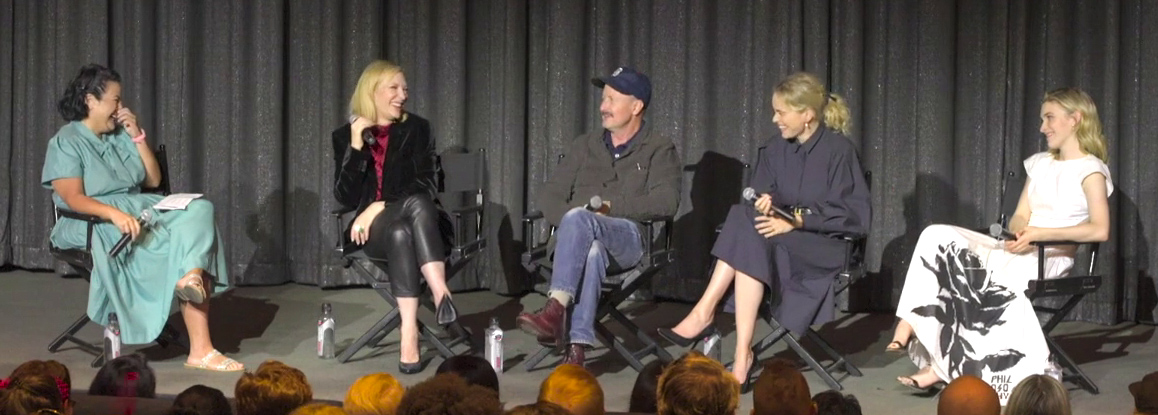

Click the image to watch the conversation with Nina Hoss, Sophie Kauer, Todd Field, and Cate Blanchett moderated by Adam Gopnik in New York (October 2nd 2022).

Variety: Actors on Actors – December 7th 2022

Beware of spoilers:

Cate Blanchett: ‘Early in my career one director used to treat me brutally’

Down the Zoom link from rural South Australia, Cate Blanchett sounds simultaneously commanding, energised, laid-back and gently self-mocking. “You’ve caught me at a barbecue,” she says. “How Aussie is that?”

Physically, she may be back in her homeland. Mentally, she is clearly still wrapped in thoughts about a role that took her deep into the heartland of European culture. In Todd Field’s new film, Tár, the American director’s first movie for 16 years, the 53-year-old actress plays a celebrated orchestral conductor called Lydia Tár, the music director of what is clearly intended to be the Berlin Philharmonic. In the course of the film Lydia’s career and family life fall apart as allegations mount about her bullying behaviour and the suicide of a female student whom (we infer) Lydia groomed sexually, then ruthlessly discarded.

“It’s not really a film about conducting,” Blanchett says. “It’s not even a film about the classical music world. In fact it’s very hard to pin the movie down, which is its strength. It’s a little bit like a Rorschach test: different people will read very different things into it. I really want people to see it and tell me what they think.”

OK, I’ve seen it, so what about this as an interpretation? Early in the film there’s a scene where Lydia totally monsters a young male music student in a masterclass at what is (we presume) the famed Juilliard School in New York. She piles on the criticism to such an extent that the student starts physically shaking. For anyone with experience of life in top conservatoires or drama schools the episode will seem painfully familiar. To me, the scene looks like a damning indictment of the destructive teaching that still goes on in some world-renowned arts colleges. Blanchett, however, sees it more circumspectly.

“Yes, it’s a painful scene,” she says. “It’s like watching a car crash. Yet it’s interesting that when we look at elite sports, when we see young athletes pushing their bodies to the limit in order to become stronger and faster, we somehow understand and respect that process, whereas we don’t accept that this also has to happen in the creative arts if you want to push through the barriers. And yes, it can be a bruising experience. I have been through it myself.”

Really? Surely it would take a very brave director to tell Cate Blanchett how to act. “Oh, early on in my career I would sometimes be treated brutally by a director in the rehearsal room,” she replies. “Yet I ended up making a massive breakthrough because of it. To be frank, I wouldn’t be here now if that sort of thing hadn’t happened. It made me think, ‘I’m bigger than this, I’m stronger than this,’ and I kept going — but perhaps I was able to do that because of the colour of my skin, or where I was in my career. The important thing is to be aware and respectful of these things when nurturing young talent.”

There are few symbols of power and hierarchy in the arts more potent than the podium on which a conductor stands, towering over the musicians in the orchestra. Yet Blanchett believes that in other artforms, too, people in power find symbolic ways of keeping junior colleagues in their place. “When I job-shared running the Sydney Theatre Company with Andrew [the Australian director Andrew Upton, her husband for the past 25 years] the first thing we did was remove the desk from our office. Andrew said: ‘This must not be a company in which the boss sits behind a desk’.”

Wasn’t that a bit impractical? Desks are quite useful, after all. “He did it because he understands the power of symbols,” Blanchett continues. “He realised that if young or emerging actors entered the room and saw the artistic directors sitting behind a desk they could feel intimidated, and that would be an impediment to deep and frank conversations.”

That scary masterclass scene in Tár is crucial in another way too. It captures, in microcosm, the huge culture-war argument raging in the arts and education worlds about “decolonisation” — about how much students should be taught to revere the pantheon of “dead white males” who dominate (or used to dominate) the accepted canons of music, literature and theatre. In the masterclass Lydia, who has just turned 50 and is steeped in dead-white-male culture, is infuriated by the student’s dismissal of Beethoven as a composer worth studying. As Blanchett points out, that’s a confrontation that you might witness today in any conservatoire and drama school.

“There are student actors in London right now, at Rada and the Guildhall, refusing to study parts of the classical canon because they find the plays repugnant,” she says. “Lydia grew up in a completely different era, so she is utterly out of step with this young student.”

So is Tár also a film about “cancel culture” — people attempting to suppress views they don’t share? “At the moment you can’t create a film, novel or play without it being in some way about cancel culture or the repercussions of the MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements,” Blanchett replies. “That’s the world in which we are all making work. For Lydia in this film the exultation of serving the music is all-consuming. How she gets results, and how she behaves to other people, is of secondary importance to her. However, that’s not something that is accepted today. She is the right person to do her job, but she is living at the wrong time. Therein lies the tragedy.”

The most emotionally fraught part of the film deals with Lydia’s growing obsession with Olga, a young cellist in her orchestra (brilliantly portrayed by a 20-year-old British-German cellist, Sophie Kauer). It’s a fixation so intense that Lydia manipulates an audition process so that Olga, rather than the orchestra’s principal cellist, ends up playing the solo part in Elgar’s Cello Concerto.

On first sight, at least, this looks like a classic case of MeToo misconduct: a powerful conductor pulling strings to promote a young musician in return for expected sexual favours. The film even makes reference to James Levine, the real-life conductor of the Metropolitan Opera in New York, who was fired after a string of allegations about sexual misconduct with young musicians.

Yet here again the film presents the relationship in an open-ended, almost ambiguous way that leaves audiences uncertain about who is using whom. Olga is no innocent, and it’s made clear that she is quite prepared to deploy her charms to get on in the music world. And Blanchett suggests that there is a completely different way of looking at relationships between older, powerful people in the arts and young protégés.

“When I first saw Death in Venice [Visconti’s film of Thomas Mann’s novella] I thought it was about a creepy old man having designs on a young boy. In preparation for making Tár I watched it again, having not seen it for 25 years, and it was as if I was watching a completely different movie: one that was all about mortality and grief and loss. Because I was at a very different time in my own life I had gravitated towards a completely different understanding of the same story. And that’s how I view Lydia’s relationship with Olga in Tár. To say it’s about sexual desire is reductive. It’s as much about Lydia wanting to reclaim her own youth, to identify with someone only just starting her career.

“And of course that fits in with the music Lydia is conducting. She is rehearsing Mahler’s Fifth Symphony, the piece in which Mahler is looking at young love through the eyes of an older person.”

It’s most unlikely that the story of Tár would have been conceived 30 or even 20 years ago. The premise that a woman conductor could rise to a position of power with a leading orchestra, especially in Germany, would have seemed unbelievable. As Blanchett points out, the advance of women to the highest positions in classical music — or most artforms — didn’t pick up steam until the last decade of the 20th-century.

“Not a single female was in authority in any major classical orchestra until the 1990s,” she says. “The Vienna Philharmonic didn’t even admit women players until 1997. The situation is completely different today in all the arts. I personally don’t even think about my gender until I am confronted by it — until someone reminds me to put me in my place, or tell me what is possible or appropriate.”

It’s hard to imagine even the most unreconstructed chauvinist pig having the nerve to lecture Blanchett about where a “woman’s place” is — but apparently one did, and recently too. “When we were rehearsing a scene for Tár with the Dresden Philharmonic, a male conductor came up to me and said: ‘Actually, you are quite a good conductor.’ I replied: ‘Oh, that’s nice, thank you.’ Then he went on: ‘Yes, probably better than most female conductors in real life.’ I laughed because I thought he was joking, but it turned out he wasn’t. He carried on, in such a boring, disrespectful, banal, generic, pre-digested, old-fashioned way that eventually I said: ‘I think you should stop right now.’”

What comes across most powerfully in Tár is how quickly a creative artist at the pinnacle of her fame and power can suddenly find her whole life disintegrating. Again, one can find examples of that all around the arts world: people who achieved early success, then started to believe their own hype. “It’s what happens when you become fractured from your roots,” Blanchett says. “Lydia has become so enmeshed with institutional power, so overly concerned about her legacy, that she has forgotten where she came from and who she actually is. She has embellished the story of her origin to such an extent that she has become estranged from herself.”

And estranged, too, from her wife and daughter. She ends up in Thailand conducting an orchestra that supplies the backing track to video games. It seems like the ultimate degradation, but Blanchett feels the film’s ending is actually rather optimistic. “This is Lydia’s chance to start all over again: just her and the music, without all the baggage.”

Blanchett’s ferocious work schedule — more than 70 films in 32 years, plus dozens of stage roles ranging from Hedda Gabler to Blanche DuBois — means that she has already completed another couple of film projects since Tár. “The latest is with Warwick Thornton, a director I’ve long admired, and it’s called The New Boy,” she says. “It’s set in 1940s Australia and is about the intersection between indigenous spirituality and Christianity.”

Having immersed herself in the classical-music world so intensively with Tár, what parallels can she draw with her own artform? “Not so many with the film industry, perhaps, where there are a lot of processes involved before audiences get to see your work,” she replies, “but there are many similarities between live concerts and live theatre. As an actor in a stage play you are also alive to the moment, to the ensemble around you, to the audience, to how the show is being received, how it is shifting from moment to moment. And also, when you come off stage, whether you are an actor or a rock musician or an opera singer, you have that experience of being in a slightly altered state. The electrifying thrill of performing live in front of an audience has changed you somehow.”

Now that Blanchett has created such a persuasive portrayal of a conductor in a film, would she consider more projects involving music? “Oh I don’t know,” she replies. “I have so many friends who are renaissance people. They can paint, sing, dance, act. I can only do one thing! I’ve been ploughing that furrow like crazy because it’s the only furrow I’ve got.”

Full interview on The Times

Cate Blanchett recalls the moment after she said yes to ‘TÁR’

Cate Blanchett was in Budapest, filming video-game adaptation Borderlands for Eli Roth, when her agent called to say Todd Field had written a script especially for her. “We had met maybe 10 years ago, on a project he was doing with Joan Didion, and for one reason or another it didn’t happen,” recalls Blanchett of Field. “But he doesn’t leave the house very often to write and direct. It’s a rare thing. So my agent said, ‘I think you should read it quickly.’ She doesn’t say that very often. She’s only said it once or twice. I read it immediately and I couldn’t put it down.”

TÁR, Field’s first film as writer/director since 2006’s Little Children, tells the story of Lydia Tár, a pre-eminent concert conductor and EGOT winner, who is preparing to record Gustav Mahler’s ‘Symphony No. 5’ with her Berlin orchestra. But as spectres from the past return to haunt her, the highly strung and volatile Lydia’s personal and professional lives unravel, resulting in a devastating fall from grace.

“I was bamboozled by it,” says Blanchett of Field’s script, which touches on issues of #MeToo, cancel culture and the corruptive nature of power. “You open the page and here comes an eight-page monologue about a whole lot of things I only vaguely understand, with terminology I had never heard, and I realised it made existential and rhythmic sense to me before it made intellectual sense. It haunted me. I said yes straight away. Then I got the knee sweats and realised just how much work I had to do.”

She jumped right in, learning piano, how to conduct and wield a baton. “Because of lockdown, a lot of musicians were unable to perform, which was an incredible gift for me, selfishly,” she says. “During the day, I was kicking and punching and flying through interstellar space. In the evening, I was having piano lessons and Zooming my friend [conductor] Natalie Murray Beale to dissect Mahler’s ‘Fifth’ and work out which pieces we should conduct in the rehearsals. It was an incredibly schizophrenic but exciting way to prepare.”

An education

Blanchett trawled through online rehearsal videos and masterclasses. “Thank God for the internet and YouTube. I started with the masterclasses of [Russian music teacher and conductor] Ilya Musin, because the first person I met was the conductor of the Scottish National Opera and he trained with Musin. He said to me, ‘It’s all about breath.’ In that way, it’s not so dissimilar from acting. The backstory of the character is she was a child of deaf parents, so I thought about sign language influencing her style. There were so many things brought to bear beyond simply learning that the right hand does the beating and the left hand does the expression. Anytime she was conducting, I wanted it to be as dynamic as possible and to advance the drama. Conducting is all about communication.”

It was Blanchett’s idea that Lydia speaks German to her musicians, despite at the time having only a school-level knowledge of the language. “Todd had said early on that he wanted to be a fly on the wall, he wanted to feel you were bearing witness to these rehearsals, to these people’s lives, so I said to him, ‘I’m making a rod for my own back, but she has to conduct the rehearsals in German. There’s no way she wouldn’t — it would be disrespectful. A friend put me in touch with Franziska Roth, who teaches opera singers to sing Wagner. She understood the language, the musical language, and was an enormous help.”

Lydia is an indelible creation: abrasive, petty, acerbic, deeply flawed, selfish, totally lacking in self-awareness, monstrous. Blanchett’s committed performance saw her scoop the Volpi Cup for best actress at Venice, where TÁR premiered in September — ahead of the film’s North America release via Focus Features in October.

“Powerful forces move through a conductor. That’s why they’re called conductors, I guess,” muses Blanchett. “Even before I got to the end of the story, I thought, ‘What is she running from? Does she know how to be herself?’ She’s someone who believes in the ability for human beings to be transfigured by genius, who has surrendered and devoted herself to the supreme God of music, at great personal cost. The character is about to turn 50, which is enormous, and I always saw her as being in transition. She’s got to accept there’s this change happening.”

A birthday party sequence was shot, which “was extraordinary. But that whole thing has been excised from the film, and it’s only there in a subtle way. But I was very aware of that fact.”

Extended takes

Working with Field was, she says, “very symbiotic”. Many scenes were shot in extended takes. “We goaded one another creatively, to go outside our comfort zones, in ways I’ve experienced in theatre but rarely in film,” Blanchett reveals. “He is one of the great screenwriters, so there was an incredible architecture of the story to hold us. And within that, his preparedness to improvise, to see what happens, and to throw everything we had in our arsenal, was exhilarating.”

Blanchett is an executive producer on TÁR, a role that has come to the fore for her in recent years with Carol and miniseries Stateless and Mrs. America. “I spent a decade with my husband [Andrew Upton] running a very large cultural institution in Australia and had an incredible creative surge doing that,” she explains, with reference to the Sydney Theatre Company. “What has been waning, in terms of the respect for it, value for it and space for it, is the creative producer. People who understand how things are made, who have a sense of the whole, not just their part within it.”

“I have always, as an actor, been interested in the whole,” she continues. “That’s why I’ve played characters who died on page nine, and characters who’ve been in every frame. Creative producing, being the friend of the director, I find incredibly exciting. I don’t have to be in it.”

With Upton, Blanchett is producing Apples director Christos Nikou’s English-language debut Fingernails and developing a film of 1960s TV show The Champions with Ben Stiller. As she speaks to Screen International, she is back home in Australia for the first time in four years, starring in and producing feature film The New Boy for Warwick Thornton “about the intersection between Indigenous spirituality and Catholicism. He’s an Indigenous director I’ve always wanted to work with.”

Blanchett plays a nun — a long-cherished ambition, she reveals. “I watched a film years ago where Hayley Mills burnt down a convent and I thought, ‘Oh, being a nun would be so exciting,’” she laughs. “I’ve since watched documentaries about the Carmelites… and maybe not.”

Welcome to Cate Blanchett Fan, your prime resource for all things Cate Blanchett. Here you'll find all the latest news, pictures and information. You may know the Academy Award Winner from movies such as Elizabeth, Blue Jasmine, Carol, The Aviator, Lord of The Rings, Thor: Ragnarok, among many others. We hope you enjoy your stay and have fun!

Welcome to Cate Blanchett Fan, your prime resource for all things Cate Blanchett. Here you'll find all the latest news, pictures and information. You may know the Academy Award Winner from movies such as Elizabeth, Blue Jasmine, Carol, The Aviator, Lord of The Rings, Thor: Ragnarok, among many others. We hope you enjoy your stay and have fun!

Black Bag (202?)

Black Bag (202?) Father Mother Brother Sister (2024)

Father Mother Brother Sister (2024) Disclaimer (2024)

Disclaimer (2024) Rumours (2024)

Rumours (2024) Borderlands (2024)

Borderlands (2024) The New Boy (2023)

The New Boy (2023) TÁR (2022)

TÁR (2022) Guillermo Del Toro’s Pinocchio (2022)

Guillermo Del Toro’s Pinocchio (2022) Documentary Now!: Two Hairdressers in Bagglyport (2022)

Documentary Now!: Two Hairdressers in Bagglyport (2022)